Next time you see someone popping honey into their trolley at the supermarket to drizzle over their breakfast cereal or morning toast, spare a thought for the hard-working bees that have flown 55,000 miles to make just one jar. More than just a sweetener, this liquid gold is the product of a mutually-beneficial relationship with plants that’s been forged over millions of years.

Unlike their bumblebee brothers and sisters, honey bee colonies, which can contain as many as 80,000 individuals, have evolved to survive year after year. In reality, few of us are ever really as ‘busy as a bee!’ Naturally industrious, honey bees work their whole lives to provide for their hive.

Pollinating Power

A single bee colony is able to pollinate 300 million flowers each day, helping to seed everything from coffee to cotton. Critical to the world’s food security, one out of every three bites of food we eat depends on these vital crop pollinators. According to bee experts at the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, one third of the world’s food production depends on our fuzzy friends. Honey bees also deliver huge economic benefits. In America alone, they’re estimated to contribute a whopping $15 billion to the country’s GDP.

And it’s becoming even more popular than ever according to the latest Sugar and Sweeteners Outlook report published by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), which shows Americans’ appetite for eating honey has reached an all-time high.

But the ethics of consuming this liquid gold remains a sticky subject as bees are often subjected to barbaric practises in commercial hives. In reality, the honey is only as good as the beekeepers who harvest it.

In the case of biodynamic or balanced beekeeping, honey is only taken from the hive in spring when the colonies have ample food to go around. Unfortunately, larger commercial hives rob their precious colonies of their food in the autumn, ahead of the bees hibernating.

Slaughtered and starved

The helpless hive is then fed on an artificial sweetener that’s deficient in the essential micro-nutrients that honey provides. Another hallmark of industrial-sized operations is culling their hives post-harvest, because it’s cheaper than feeding their bees through the winter. An estimated 10-20 per cent of colonies in the U.S. are slaughtered either by being drowned in soapy water, suffocated in sealed bin bags that are left out in the sun, or doused in petrol and burnt alive.

The queen’s wings are typically clipped so she can’t swarm – leave the colony – which would compromise the hive’s productivity. She’ll also endure artificial insemination, which requires crushing thousands of drones to death to extract their semen

But it’s the lucrative products that beekeepers ‘scrape away’ from the hive which burdens the bees more than removing the honey itself. Taking away the royal jelly meant for the young queens-to-be-larvae is as good as stealing baby food, while extracting their antiseptic propolis is akin to pilfering the medicine the colony uses to ward off disease.

Thousands are also killed in the name of so-called ‘anti-inflammatory venom’ that’s extracted by giving an electric shock to the bees as they enter the hive.

As for the queens, they’re treated anything but like royalty. Her wings are typically clipped so she can’t swarm (leave the colony), which would compromise the hive’s productivity. On top of that, she’ll endure artificial insemination, which requires crushing thousands of drones to death to extract their semen.

Guardians of biodiversity

Honey has been tapped for its medicinal uses from skin burns to mouth ulcers for some 8,000 years but that’s not the only thing bees gift us. Key to sustaining the earth’s critical ecosystem services, these guardians of biodiversity form one link within a long chain of interdependent species. Recent studies suggest that honey bees can also improve the nutrient value of the very crops they pollinate.

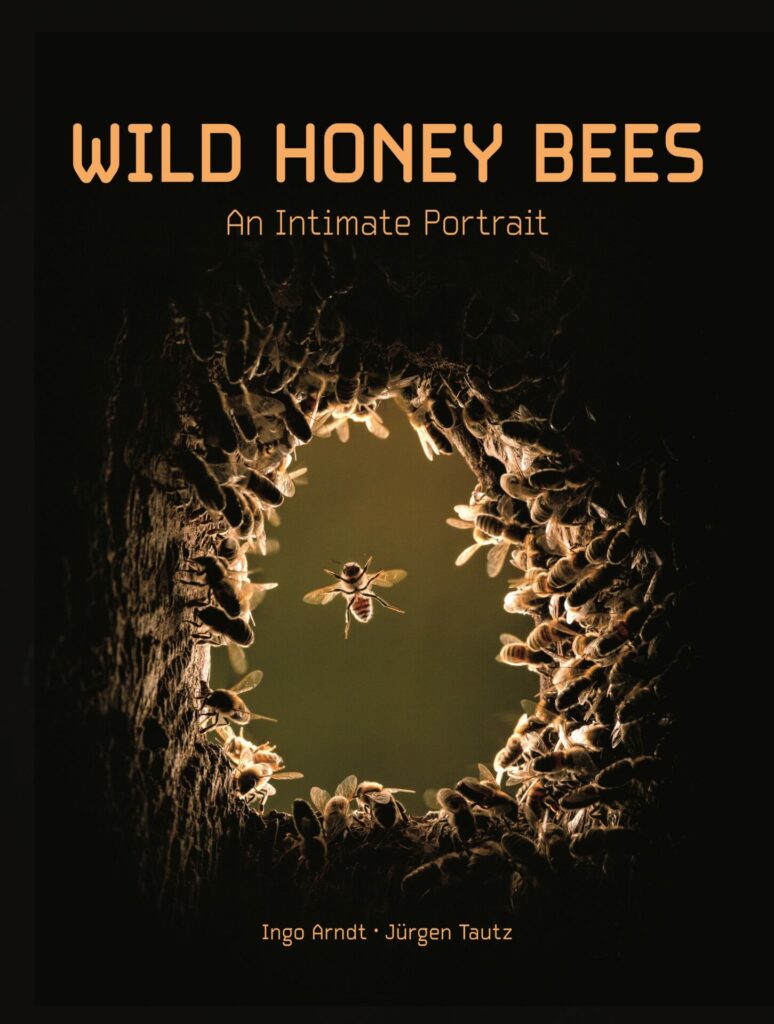

While the lives of domesticated bees are well documented, their forest-dwelling relatives are less so. The image of a hazmat-suited beekeeper tending to their stacked hives is a familiar one. Yet in reality, wild honey bees will nest in the hollow of a tree. A new coffee table book, Wild Honey Bees is the collective work of behavioural scientist Jürgen Tautz and nature photographer, Ingo Arndt. It studies how they live in harmony with the forest: from the unique symbiotic relationships they have evolved with a mite-eating book scorpion, to how they use forest honeydew to produce honey.

Thomas Seeley’s The Lives of Bees, examines the growing evidence that wild honey bees are faring better than those managed in hives. The thinking is that non-domesticated honey bees have superior genetics, giving them natural immunity to mites, unlike their boxed friends who are medicated with miticides, an agent used to kill mites.

Developing countries actually depend more on wild species of honey bees than domesticated for their crops. Meanwhile, in the mountainous regions of Middle Eastern countries like Oman and Yemen, locals have practiced ancient beekeeping traditions, involving gathering honey from wild hives, for centuries.

Four thousand miles away on Ireland’s windswept west coast, researchers from The National University of Ireland Galway are using citizen science to help plug the knowledge gaps.

Several years ago, they launched Europe’s first ever nationwide survey to collect data on reported sightings of wild honey bees. Ireland’s only native honey bee, the Apis mellifera mellifera is a strain of the Dark European Honey Bee that once thrived in Northern Europe. In May this year, a new bill was proposed to protect the threatened Apis mellifera mellifera by outlawing the import of disease-carrying non-native bees.

A Perfect Swarm

It’s not one, rather a perfect storm of human activity that threatens honey bees. The elephant in the room is our own insatiable appetite for cheap and readily-available food. Modern monoculture is to bees what eating boiled potatoes, day in day out, would be to us. In rural China, exasperated farmers have resorted to pollinating their orchards by hand after their wild honey bees succumbed to intensive farming and excessive pesticide use.

Pesticides, along with chemical fertilizers and herbicides, collectively known as agrochemicals, poison bees when they land on sprayed plants, affecting everything from their fertility to memory.

Ground-breaking research from Oxford University’s Department of Zoology suggests that honey bees are unable to fly straight after consuming ‘brain damaging’ pesticides. A step in the right direction, the European Union’s highest court ruled last May that the EU could restrict the use of three crop-yield-boosting neonicotinoid pesticides. But controversially – and to the outrage of conservationists – the UK Government authorised the emergency use of a neonicotinoid called thiamethoxam on sugar beet, this spring because the crop (which provides 63 per cent of the country’s sugar) was under threat of been decimated by yellow viruses spread by aphids.

Large-scale commercial crop production, along with urbanisation, has also led to huge habitat loss, restricting bees’ foraging range. In Spain’s north western Galicia region, wild honey bees have taken to nesting in hollow electricity polesas alternatives to trees.

Hotting Up

Believed to be a leading cause of dwindling honey bee numbers globally, climate change is the prized pollinators’ latest nemesis. Spring weather in winter causes bees to expand their colonies, which then starve when drought-stressed plants fail to produce enough nectar.

Canadian honey bees have experienced their worst losses in two decades, due to an unseasonably warm spring that allowed a mite called varroa to devastate the hives. The not so good news is, deadly parasites like varroa and nosema thrive in warmer temperatures, and have the potential to bring about Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), whereby worker bees abandon their queen.

Climate change is also encouraging some bees to buzz off to our cities. According to DEFRA (the UK’s Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs), hives in Greater London have more than tripled in the past decade to around 7,000 colonies. Meanwhile, Paris’s rooftops are abuzz with around 1,000 hives and 180 million bees happily swarm in the Slovenian capital of Ljubljana.

Urban beekeeping has also taken off on the other side of the world in sunny Sydney. But it’s not all sugary sweet. Much like unwanted Christmas puppies, first-time beekeepers can end up neglecting their hives. Established during the pandemic, Sydney Bee Rescue is an organisation set up to adopt the city’s unwanted colonies by rehoming them in rescue apiaries on pesticide-free parcels of land.

The Technology taking Flight

Closer to home, an ‘Emirati Bee’ is being bred to withstand the UAE’s unforgiving desert, which causes most hives to die off in the summer. Led by Australian scientist Denis Anderson, the eight-year-long project was founded by the Abu Dhabi Agriculture and Food Safety Authority (ADAFSA), and by crossing several different lines of one Saudi Arabian species, the team have succeeded in extending the bees’ life cycle beyond the milder months. The Emirati Bee has even been tested by the UAE Beekeepers Association: the country’s only regulated group of hobbyist and professional beekeepers, committed to bringing sustainable beekeeping to the region.

And the role technology is playing in protecting honey bees doesn’t end there. The very same science used to develop Covid-19 vaccines is being trialled by Boston-based Green Light Biosciences on hives besieged by varroa mites in states including Georgia and North Carolina. Meanwhile, in Indiana, researchers at the city’s namesake University have identified a bacterial microbe with the potential to boost honey bees’ nutritional intake. The findings could be a lifeline for colonies living near monoculture crops.