E. Mark Windle is a UK-based freelance writer, whose recent works include ‘The Hundred Year Hunger’ a study of Gaza that explores the timeline of food insecurity and malnutrition. The book also provided the inspiration for a song of the same name, written and recorded by Billy Bragg.

Mark is a former specialist dietitian, with a 25-year background in the nutritional management of patients with critical illness and major burn injuries. He used his experience to analyse the history of the Palestinian people, with regard to nutrition welfare, from the Ottoman Empire to the current Israeli war.

In the introduction he wrote: ‘While “The Hundred Year Hunger” is not intended to be a political microanalysis, it would have been impossible to present its theme – Gaza’s nutritional welfare – without political context. The two are inseparable. Constant blockades, the widespread destruction of infrastructure, and people-herding have resulted in a chronic and severe lack of access to medical and nutritional care.’

The Ethicalist caught up with Mark to explore his views on what is happening in Gaza and what lies ahead for Palestinians.

TE: How would you describe the current situation regarding food and health in Gaza and which of the population are most at risk?

The visual scenes in Gaza have been described as near apocalyptic for a while now. The nutritional and public health situation is equally dire. Last month (August 2025) famine was confirmed, and as ever, women and children are most vulnerable. Over 320,000 children are estimated to be at risk of malnutrition. Since June, between 5,000 and 6,000 children have been admitted to hospital every month for treatment of acute malnutrition.

Up to 70 per cent of pregnant and breastfeeding women are having difficulty accessing food on a daily basis. But it’s not only food that’s the issue. Folic acid is essential for normal foetal development. Iron supplements are needed to manage anaemia caused by malnutrition and pregnancy. Yet these supplements are just not getting through.

TE: How has Israel weaponised water in its ongoing war?

Before the current conflict, there were three main sources of water in Gaza: a few large desalination plants, external supply from Mekorot (the state-run company that manages Israel’s drinking water and farm irrigation)and 300 small wells. Almost all of the well water is considered unfit for human consumption, because it’s drawn from groundwater contaminated with sewage. For many, there was no choice other than to use it.

The Mekorot supply came via three mainlines connected to Israel’s National Carrier network. The taps were turned off by Israel on 9th October 2023. Instantly the output from each pipe dropped from around 1000 cubic metres per hour to zero. The supply was restored some days later following demands from the international community, but levels never returned to that of previous times.

Blockade has also severely limited truck deliveries of food and water of course. Most desalination plants have either been destroyed or, without electricity and gas supplies, are not functioning. Plants that installed solar panel fields to circumvent fuel blockades have been easily identifiable argets for the IDF.

In 2024, video evidence that was posted online (then hastily removed) showed Israeli soldiers rigging explosives to pumps at Canada Reservoir near Rafah. Its three-million litre capacity reservoir was serving 150,000 inhabitants in southern Gaza. Large water storage tanks in Khan Younis were also destroyed.

TE: What historical precedents are there for such action against Palestinians?

Weaponisation of water and food has been an issue well before October 2023. The few waterways within Gaza’s borders were never going to be enough to sustain the displaced population from the early Nakba (Palestinian displacement). Matters were made worse in 1967,when Israeli military edicts required permit applications for constructing wells. These requests were often turned down without reason, with no means of appeal.

In 2003, the goods blockade and labour constraints pushed 60 per cent of the Gazan population below the poverty line. Imported sugar, cereals and oils that had previously provided around two-thirds of typical dietary calorie needs were now extremely limited. When Hamas came to power, blockade restrictions were tightened further.

In September last year, the UK only suspended 30 out of 350 arms export licences. That’s barely even tokenism. One year on, jet fighter components are still potentially reaching Israel via indirect routes

Gaza’s fishing industry was also decimated. Israel repeatedly limited the number of nautical miles from shore that Gazans are allowed to fish. Bigger shoals and higher nutritional value fish are invariably located in deeper water, out of reach. Nowadays of course, there’s a complete maritime ban.

TE: What action would you like to see taken by Britain, the EU and the US in regard to the aid supply situation?

Aid supply will only be effective if arms supply stops and there is a sustained ceasefire. Despite the rhetoric, Britain, the US, Germany and Italy have been enablers in this conflict. In September last year, the UK only suspended 30 out of 350 arms export licences. That’s barely even tokenism. One year on, jet fighter components are still potentially reaching Israel via indirect routes.

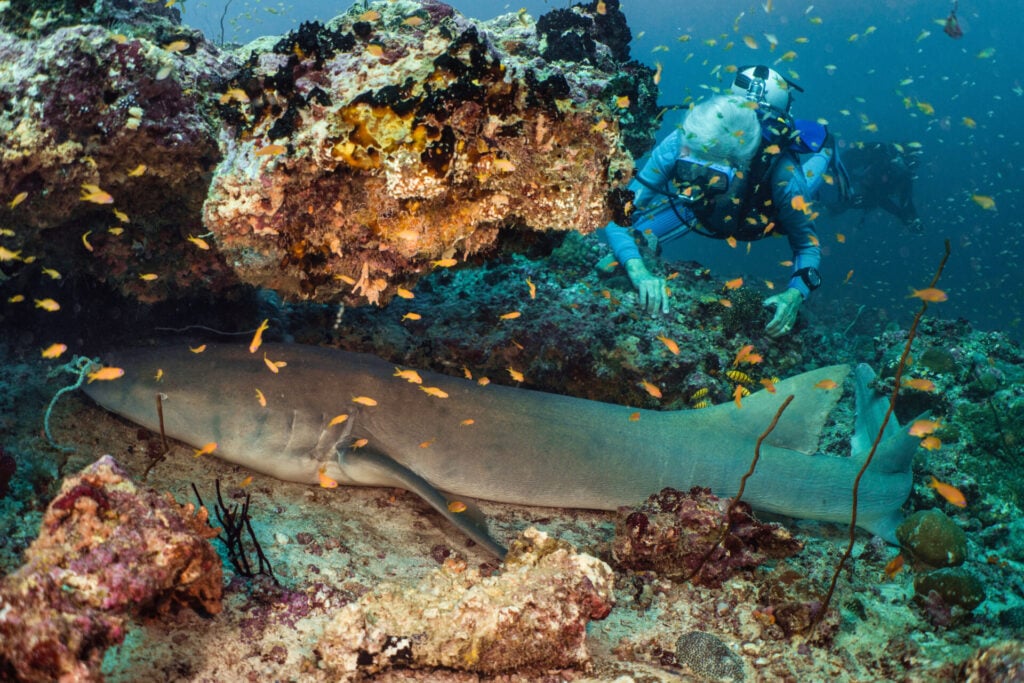

TE: How effective are projects such as the Sumud Flotilla in raising awareness of the plight of the population of Gaza?

The Global Sumud Flotilla is the latest in a long history of similar missions to keep Gaza’s struggle in the public consciousness, to attempt to break the Israeli blockade and to demand an end to the siege. The flotilla coalition is not just carrying activists. There are medical staff, legal professionals, sailors, aid workers and public figures. Fifty boats carrying an estimated 300 tons of humanitarian aid might not affect the Gaza’s situation in any sustained way, but Gaza needs all the help they can get. And even if Israel prevents any of that aid reaching the shore, the symbolism is powerful, this is an act which counters government inertia.

Cynics and armchair critics who describe the flotilla as saviourism couldn’t be further from the truth. It is an important reminder that humanity and global solidarity is still a thing. There are representatives on board from dozens of nations and at least five continents.

TE: Do you regard the actions of the Israeli military as genocide?

Without question.The Genocide Convention describes genocidal acts as those committed with intent to destroy a national, ethnic, racial or religious group by killing members of that group, causing serious bodily harm or mental harm, and deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or part. The evidence of ‘intent’ is in plain sight, regardless of the fact that Israel and the countries that supply it with arms deny it.

In ‘The Hundred Year Hunger’ I explored the evidence for genocide in the context of malnutrition. Through blockade and mass civilian displacement, illness and death rates have increased as a direct result of starvation and dehydration. Severe malnutrition impairs immune function. Consequently, recovery from gastrointestinal infection and respiratory infection is impeded. Malnutrition increases the risk of death from sepsis caused by these infectionsand from unhealed wounds.

Forced evacuation has also concentrated a population into confined areas with a high demand for limited essential resources, including food and water. Then there are the signs of intentto cause mass harm through water weaponisation, like restricting the Mekorot pipeline water supply, and the destruction of reservoirs.

TE: What do you think are the public health priorities to tackle if a lasting ceasefire achieved in Gaza?

After halting arms supply and achieving a lasting ceasefire, securing an ongoing and coordinated flow of food, water, clothing, shelter and medical aid is essential. The establishment of potable water and sanitation systems is another immediate priority.

Gaza’s rebirth will be a case of starting from scratch rather than picking up from where things were left. Intervention must be timely but also sustained. Rebuilding of residential and municipal infrastructure and reinstatement of public health services to support nutritional, medical and psychological needs should be at the fore.

Comprehensive screening will be required to assess the nutrition status of the wider population. A lot of the data so far as been derived from smaller samples in specific geographical areas, as the conflict has limited the ability for health professionals to access civilians in difficult to reach areas. Wider knowledge of the prevalence of muscle wasting, anaemia, vitamin and mineral deficiencies will help guide public health interventions.

TE: Lastly, what do you think of Billy Bragg’s song?

I admire public figures who are fearless in demonstrating their concerns regarding social and civil injustice. Billy is a fine example of that. He has a decades-long track record of using his platform to support causes of under-represented groups, and has worked tirelessly with various anti-fascist, anti-racist and anti-war movements.

I was truly humbled to hear from Billy that ‘The Hundred Year Hunger’ inspired him to write a song for Palestine and to show his solidarity with the Global Sumud Flotilla. The song’s narrative takes the listener throughthe Palestinian affinity to the land, and the long history of occupation and oppression of Gaza’s people. Billy also references the current conflict and famine while highlighting that even in Gaza’s darkest hour, existence is resistance. I wish him well with the song.