How a charity is trying to save an escaped beluga whale thought to have been trained as a secret agent by the Russian military

When an underweight beluga whale was spotted following trawlers off the North Norwegian coast, several miles from Hammerfest harbour, fishermen were puzzled. The shy, skittish arctic-dwelling marine mammals rarely venture so far south and generally avoid boats and people.

But this one actively sought human contact and hungrily accepted food from humans. And it was also fitted with a harness. Something fishy was going on.

The whale, fishermen surmised, had escaped from captivity.

Four days later it took up residence in the harbour and started playing with locals. A feeding programme was established. Meanwhile Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries inspector Jorgen Ree Wiig donned a survival suit, jumped into the icy water and removed the harness which, surprisingly, was fitted with a camera mount and marked with the words ‘Equipment St. Petersburg’.

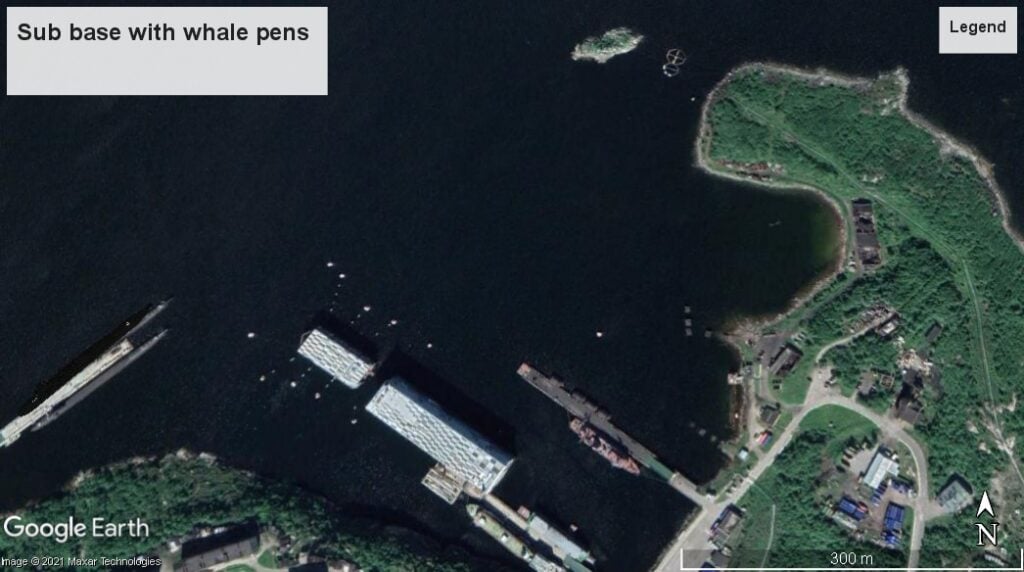

That was April 2019 and the incredible story that unfolded in the following months was straight out the pages of a cold war thriller. Evidence suggested that the whale was a Russian spy which had escaped from a secret marine mammal training facility located several hundred kilometres away near the Russian naval towns of Murmansk and Severomorsk. Satellite images showed penned beluga whales being held at the secret military base.

Secret Agent

While it is not known whether he sprung himself from his pen or bolted while on manoeuvres in the Barents Sea, satellite images back up the theory that the beluga is a secret agent.

His former home was likely Olenya Guba, a secret submarine base in the Kola Bay estuary that is home to Russia’s 29th Special Submarine Squadron, operated by the Main Directorate for Deep Sea Research, nicknamed GUGI. A fleet of spy-submarines based there include several nuclear-powered vessels suspected of being used to spy on the West and to seek out seabed communication cables.

Satellite images of the base from 2019 show several circular whale pens moored there. One image from April 2019 shows two pens moored at a pier next to a naval ship at the base. A white whale is visible in one. The vessel is an intelligence ship that carries two small submarines, officially said to be used for ‘deep-sea research and rescue operations’. It is known that marine mammals used by military forces are transported over distance in special slings aboard such boats.

The Russian Ministry of Defence placed an order for five dolphins raising speculation that it had revived a programme to transform them into marine scouts and assassins

The Russian Navy is cagey about their current use of marine mammals for covert operations, thought to include surveillance, but it is known that they have trained dolphins, sea lions and whales for missions since Soviet days. Belugas are known to have been used to guard naval bases, help divers and find lost equipment.

Indeed, documents uncovered in 2016 show that the Russian Ministry of Defence placed an order for five dolphins that year, raising speculation that it had revived a programme to transform the creatures into marine scouts and assassins. A detailed tender document published on a government website offered 1.75 million roubles for two male and three female bottlenose dolphins up to 2.7 metres long. It is believed that GUGI took over a Soviet-era Crimea-based training programme being run by Ukraine when Russia annexed the region in 2014.

Russian officials deny the whale was their spy. One spokesman claimed he was an escaped therapy whale used to help sick children, while another suggested he had in fact originated from St Petersburg in Florida.

Meanwhile in Hammerfest he was promptly named Hvaldimir, a portmanteau of the Norwegian word for whale (hval) and Russian president’s name. For several months he lived in Hammerfest harbour, where he sought human contact, showed a complete lack of caution around boats, and became a tourist attraction, with up to 300 well-wishers a day visiting.

This created a dilemma for officials. Hvaldimir was a large, breeding age male who, while appearing friendly, did have a habit of gently tugging at the fins, legs or arms of some of those who swam with him. His interest in boats and machinery put him in danger and he received several injuries after people gave him pieces of wood or sharp objects to play with.

When Hvaldimir relocated himself to salmon farms further up the coast the problems persisted. The tourists followed and the farm owners accused Hvaldimir of scaring the fish and jeopardising the safety of their operations. Some even spoke of killing him.

Oslo-based filmmaker Regina Crosby arrived in 2019 to film him and assumed it would be a short story about a whale that had escaped captivity and was now safe from harm. But she was troubled by what she saw. Hvaldimir continually followed farm inspection boats, swimming around and under them. Despite public warnings, people persisted swimming and snorkelling with him, following him in boats and disturbing him after he learned to catch fish for himself.

One Whale

Regina stayed in Hammerfest and founded One Whale, a charity that aims to relocate Hvaldimir into his own safe, protected fjord and create a nature reserve for him and other whales who have been rescued from concrete tanks. It is hoped that one day Hvaldimir could even be rehabilitated and released back into the ocean as a wild whale.

Hammerfest municipality backs the scheme and has assigned a fjord in which the reserve can be located. The One Whale team are now fundraising for the infrastructure needed to turn the vision into a reality. And in the meantime, Regina created ‘Team Hvaldimir’, a public safety program to protect the health and welfare of Hvaldimir by educating the public and cultivating a working relationship with the salmon farms.

Today, three years after he first arrived in Norway, Hvaldimir’s future looks promising. The authorities in Norway have accepted that he is not a wild whale, which makes placing him in a reserve a matter of protection.

As Regina explains: ‘It is obvious when you look at a wild beluga and you look at Hvladi who lives under a salmon boat every day of his life, that he’s not wild. Nonetheless it’s important to state this in our goal of protecting him, which involves keeping the public away from him. We are not taking a wild whale and putting him in captivity. We are very much anti-captivity. Our mission is to protect him and give him the chance of a life that’s a little wilder than the one he’s leading now.

‘We have the offer of this entire gorgeous pristine fjord that will be dedicated not just to Hvladi, but to other whales in captivity whose owners are looking for places to release them. This is a forever project and its hoped Hvladi will be the first guest.’

Norwegian Whale Reserve

The project will be named the Norwegian Whale Reserve. It will be the first of its kind in the world and One Whale is now in the process of raising funds to buy equipment, boats, and build the docks, pontoons, surveillance system and netting that will be required to keep Hvladimir safe. A pontoon, vet accommodation and netting alone is estimated at around 2m Euros.

Until the reserve is established Hvladimir’s safety continues to be a concern. Last summer as many as 300 tourists a day arrived to see him. Now Norway’s open for tourists Regina worries the numbers will increase.

‘We’ve seen people give him sharp things and pieces of wood. An unfortunate consequence was that last summer he had a bad mouth injury that could have killed him were it not for the vet care we have put in place.

But despite his legions of fans, the spy whale still divides opinion in some quarters. Regina discovered recently that an application had been made to cull him.

‘We found out that someone had applied for a permit to kill him after some rubber underwater hoses running fresh water into some cabins had been tampered with and he got the blame. Thankfully the request was denied.’

The sooner he gets to settle in the reserve, the safer he’ll be. ‘If he’s given enough time, and especially if he’s around other whales, he may become less imprinted on humans,’ says Regina. ‘This isn’t fair. If you saw a lost dog living under a dumpster you would help it. A stray whale doesn’t come along that often. Hvladi is a domesticated animal and it’s not his fault he came here. We owe it to him and the other whales this project will potentially help to do everything we can to create a better future for them.’