As the CEO of a billion dollar company, Savji Dholakia likes nothing more than digging very large holes and filling them with water. Indeed, when he was growing up in rural India, and forced to leave with his three brothers to find work, it’s something he vowed he would do.

‘Every year you could see the water levels around our village just get less and less, and how the village started shrinking as a result of this lack of water to drink, to farm with,’ he recalls. ‘Even as a child, I think I had some idea that if I ever made any money I would go back and do something about it.’

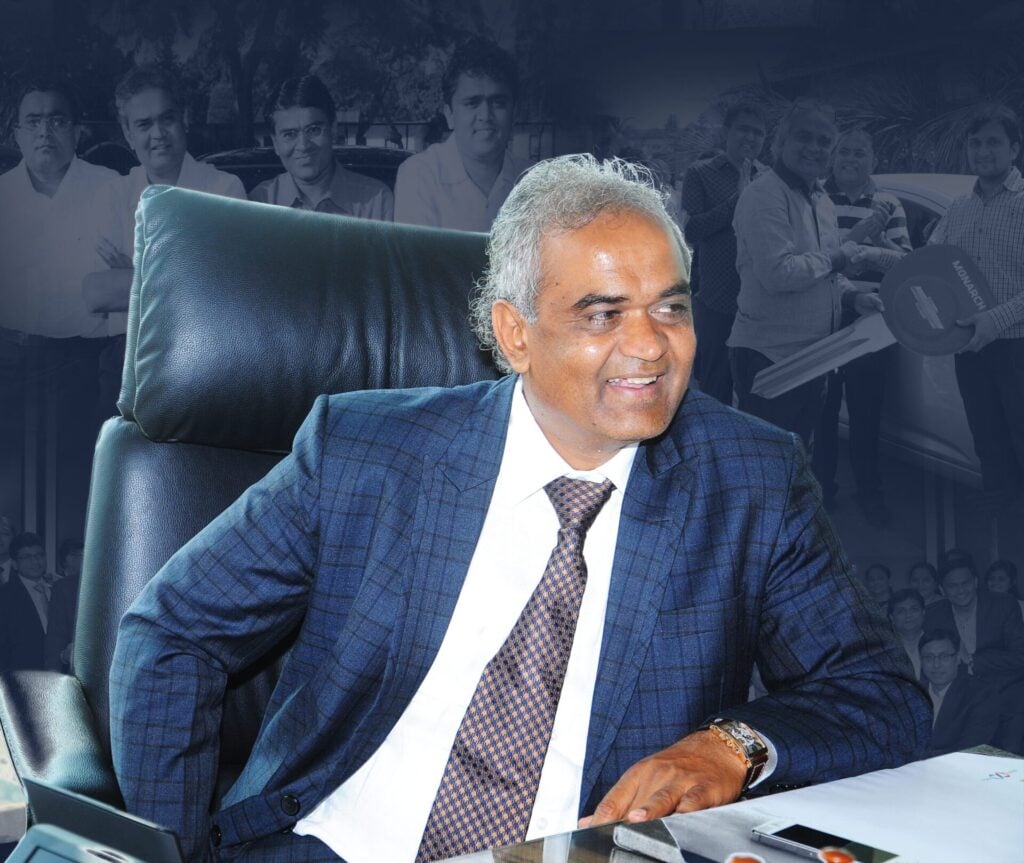

And that he has, in a spectacular way. His business may be diamonds – he apprenticed in diamond cutting and polishing before co-founding his Hari Krishna family firm in 1992, now India’s largest exporter of diamonds, supplying the likes of Tiffany & Co and the Signet Group. But now in his 60s, nearly all his time is devoted to his Dholakia Foundation, which has created over 100 lakes across Gujarat, his home state in western India. These are huge projects too. Each is around seven million square feet and 20 feet deep.

‘That’s why we have our own JCBs, trucks, tractors, even a fleet of petrol tankers so the work can go on 24/7,’ enthuses Dholakia, who has supplemented his water management programme with the planting of 2.5 million trees. ‘I didn’t stay at school beyond fourth grade so didn’t even do basic maths, so it’s not as though I know a lot about advanced planning or engineering. But over your years you do get a lot of experience and learn to delegate well. I think being on site is when I’m the happiest I’ve ever been.’

‘We have thousands of people across India who don’t have access to clean drinking water, despite the fact that India isn’t short of water sources, just the commitment to make them accessible to the people who need them,’

Savji Dholakia, founder Dholakia Foundation

The consequences have been spectacular too. The 13 billion litres of water these lakes have made available have been transformative for some 200,000 small farms. Cotton production across the state, for example, has increased five fold.

‘What’s the one dominant thing that nobody can survive without? Water. And yet we have thousands of people across India who don’t have access to clean drinking water, despite the fact that India isn’t short of water sources, just the commitment to make them accessible to the people who need them,’ Dholakia explains. ‘And water has a knock-on effect for communities, their income and self-sufficiency, their agriculture, how they in turn can save other resources. I’ve seen villages get good water supply and become empowered by it.’

It has also, he feels, set an example – maybe even an embarrassing one – that has since encouraged the Indian government to mandate its own lake building across the country’s other states. ‘I think there’s a kind of pressure by example, even a motivation to those areas where there is water scarcity to take action themselves,’ reckons Dholakia, who was invited by the United Nations in 2023 to its first water conference in almost 50 years.

The Dholakia Way

It’s an approach he also likes to take within his company too, with its $1.5bn turnover and 6000-plus employees. His minimal education has, he says, not only made him a self-starter – he concedes that he knew nothing about building lakes but that this also didn’t stop him – but afforded him an unconventional take on management.

Take weddings, for example. Every year the company arranges and pays for mass weddings for the sons, daughters or even siblings of its employees who might not otherwise be able to afford one – the current record is 78 hitchings in one go. And then there is its quirky bonus scheme. Sure many companies reward good work with extra pay. But, Dhloakia explains, Indians prefer more visible, symbolic expressions of their being valued.

That’s why, 20 years ago – when the company was turning over just $165,000 – he gifted three cars to particularly hard-working employees. In 2014 he decided to put this policy on an official footing and gifted 500 cars, and 207 houses. It has not been unknown for the company to buy 1,000-plus cars a year as employee rewards.

‘We get a lot of emails from dealers who want to make contact with us. Not just car dealers, in fact. Anyone who makes homewares seems to know where we are too,’ laughs Dholakia, adding that he pushes for decent discounts for his unusual bulk-buying.

‘But I really believe when there’s some kind of genuine bond between employer and employees that’s better for both,’ he adds. ‘We try to develop a family culture and people who work for the company I think know it comes from the heart. And, to be honest, we see our production increase as a result too.’

Each young family member intending to join the family firm is sent to live in a major city for a month – without income, employment, and prohibited from using the family name to pull strings

It’s this spirit of what what western employees especially like to brand as ‘corporate social responsibility’ – but which in Hari Krishna’s case seems that bit more intimate – that Dholakia is keen to maintain with the next generation of the family. Dholakia says he knows this won’t be easy: much as he grew up in poverty, with little schooling, so his children and nephews have MBAs from New York universities and will inherit a fortune.

Almost inevitably, the Hari Krishna solution is a deeply unorthodox one. Many cultures around the world have their rites of passage into manhood, some of which involve being sent out alone into the wilderness. Dholakia came up with his own. Each young family member intending to join the family firm is sent to live in a major city for a month – without income, employment, and prohibited from using the family name to pull strings.

‘I think it’s a good way for them to start to learn their worth and the value of money – without the family to back them up – so that when they do go back to our company they have at least had some experience of the world out there,’ he says. ‘It’s not so hard to send your nephew out like that but I had to do a lot of work to convince my wife we had to send our son out some time too.’

He can only hope the next generation shares his enthusiasm for giving back, and for digging, as well.