Connecting spaces for animals to run, swim and fly freely and safely; wildlife corridors can be as small as a garden hedgerow or as big as a Sub-Saharan African savanna. Nicknamed ‘nature’s highways,’ these life-nurturing corridors – found both in wilderness areas and our metropolises – span land, sea and sky.

They bridge habitats for reptiles, birds, mammals and invertebrates across the world, from endangered scarlet honeycreeper birds in Hawaii’s mountain rainforests to hundred-strong herds of migrating moose traversing the American West.

But increasingly splintered landscapes due to deforestation, urban development, pollution and industrial agriculture is taking a wrecking ball to them.

This is bad news for critters big and small, who rely on them for foraging, breeding, establishing territory and seasonal migrations. Man-made barriers from fences and freeways to farms and factories pen in wild animals, cutting them off from prey and potential mates in the process.

But artificial structures can also be part of the solution. In Malaysia’s island-state of Penang, spectacled leaf monkeys are navigating their threatened tropical home with the help of fire hoses repurposed as canopy bridges.

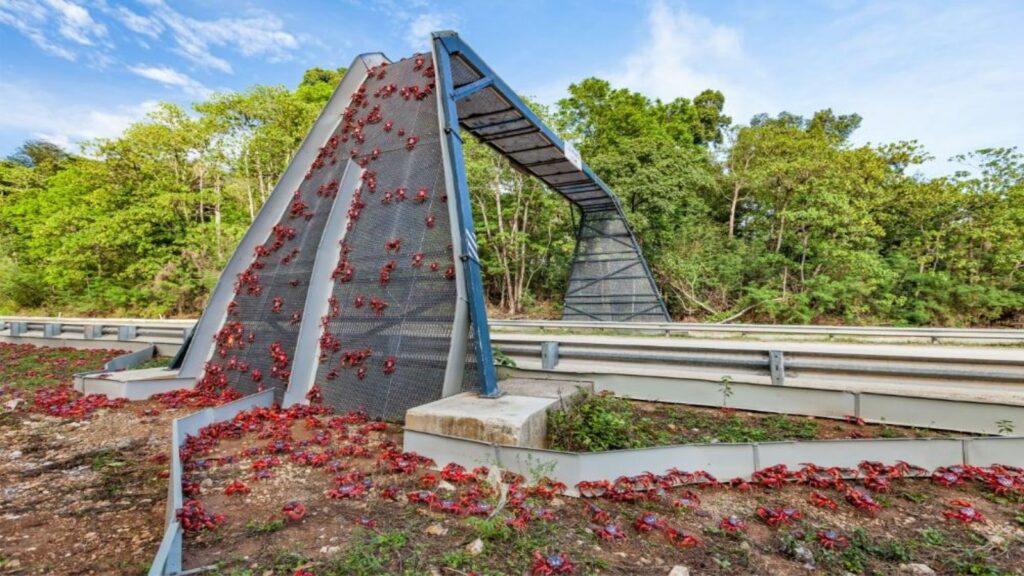

Meanwhile, on Australia’s Christmas Island, its famous red crustaceans scuttle from inland forest to sea on their annual migrations using custom-built crab overpasses.

Not all wildlife corridors are visible, to the human eye at least. The protected Cocos-Galápagos Swimway – an underwater superhighway measuring 450-miles and tethering Costa Rica to the Galápagos islands – is proving a lifeline for migratory sea turtles and sharks.

Indigenous Know-How

Habitat connectivity plays a critical role in conservation and vice versa. Huge in scale and ambition, the Y2Y Initiative is linking a 320-acre transboundary mountain area from America’s Yellowstone National Park to Canada’s Yukon Territory, where wolves, bison and caribou roam.

To date, Y2Y’s created 177 animal crossings – a mix of bridges, tunnels and trails – across a network of wildlife corridors, to try and relink isolated populations of an iconic keystone species: the grizzly bear. Approximately one quarter of the project is either managed or co-managed by indigenous groups, whose knowledge and input is key to understanding nature’s highways.

In Australia, the Eastern Kuku Yalanji people and rangers, with the help of environmental non-profit Climate Force, are quite literally growing a wildlife corridor by planting 360,000 trees to reunite The Great Barrier Reef to the 180-million-year-old Daintree Rainforest.

7,500 miles away in the sweeping plains of Kenya’s Amboseli National Park, 1,000 landowners from the Maasai community agreed last year to lease 29,000 acres of their own land to forge a wildlife corridor between the Greater Mara and Amboseli. Named Illaingarunyoni Conservancy, it will protect rare species like the bat-eared fox, African wild dog, pangolin and enable the movement of some 2,200 endangered African savannah elephants; themselves essential ecosystem engineers.

The Big Game Puzzle

In Africa, even protected reserves can become islands, leading to inbreeding and loss of genetic variation in wildlife populations, affecting their ability to survive and reproduce. In some cases, this isolation leads to local extinctions.

‘Over one hundred years ago, South Africa, much like the UK and Europe, decided to separate their wild areas from their people. The downside is the wildlife isn’t able to migrate in the patterns they used to,’ co-founder of non-profit Wild Tomorrow Fund John Steward tells The Ethicalist. Together with his wife Wendy Hapgood, he’s tethering two wildlife reserves – UNESCO World Heritage-listed iSimangaliso Wetland Park and the Munyawana Conservancy – in South Africa’s coastal KwaZulu-Natal province.

‘Our region has this very rare, critically endangered ecosystem type called the Dry Sand Forest. A lot of that has been destroyed for farmland,’ Hapgood reveals. Stitching together the habitat with a 3,170-acre corridor they’ve named The Greater Ukuwela Nature Reserve (GUNR), is no mean feat. ‘Like a puzzle, we had to wait years for some pieces of land,’ Steward says, who explains that the first piece of the jigsaw was a plot destined to be slashed and burned for a pesticide-leaching pineapple plantation.

But the couple’s patience and perseverance has started to pay off. ‘We have a [1,250] species list that keeps on growing! Leopards are very abundant and giraffes are also thriving [in Ukuwela],’ Hapgood says. ‘We reintroduced eight giraffes [to the reserve, which previously had none]. Now we’re into the thirties! That’s proof that given space and the resources they need, the wildlife will do just fine,’ Steward adds. ‘If we can just connect these places with a thin piece of land then wildlife will start being able to manage itself. At the end of the day, what we want to do [eventually] is step back,’ he continues.

Wildlife Corridors Take Off

It’s not just charismatic megafauna that depend on wildlife corridors, but the planet’s invisible insect populations too.

In northeast Scotland’s seaport city of Aberdeen, 50-acres of unloved council-owned land is being transformed into a network of buzzing, blooming wildflower meadows. ‘Since the 1930s there’s been a huge decline in the amount of our flower-rich grassland within the UK,’ Buglife Scotland’s Conservation Officer Ruth Quigley tells The Ethicalist. ‘Without the ability to move around freely through joined-up habitats, pollinating insects are at greater risk from threats such as climate change, urban spread and changing land use,’ she continues.

Launched last March, the Aberdeen B-Lines Project – a collaboration between UK-based conservation charity Buglife andAberdeen City Council – will expand foraging and nesting sites for insects like the Clarke’s Mining Bee and Early Nomad Bee. ‘A wide range of pollinators will benefit from this project, from bees and butterflies to moths, wasps and flies,’ Quigley adds. She hopes these flower-dense insect pathways will also ‘have a positive impact on the wellbeing of local people,’ who will be able to enjoy the wildflower habitat at 12 different sites across the city, including Aberdeen’s Beach Esplanade and riverside Seaton Park.

Creating, reviving and protecting wildlife corridors doesn’t happen overnight, but their benefits to animals, ecosystems and even people, are far-reaching. The WWF-supported Khata corridor – an eight-mile-long passageway linking India’s Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary with Nepal’s Bardia National Park – has been hailed a transboundary triumph. Not only has it helped wild rhino and tiger populations rebound through the expansion of community forest, but it’s provided sustainable income streams for locals too.

Meanwhile, in California, the world’s largest wildlife crossing – Wallis Annenberg – is set to provide safe passage to mountain lions across a 10-lane Los Angeles freeway when it opens early next year.

7,500 miles away, a 410,000 (and counting!) tree planting project called the Bangalow Koalas Community Wildlife Corridor – has been a hit with furry marsupials near the town of Bangalow in Australia’s New South Wales Northern Rivers region.

In another win for wildlife, last November marked the return of endangered chinook salmon to Oregon’s Klamath River after a century-long hiatus. This is thanks to the removal of a monster Californian dam, which freed up 400-miles of new habitat.

Connected really does mean being protected, whether that be through restoring an ancient nature highway or building a new one with human intervention and innovations. Wildlife corridors not only strengthen biodiversity but can sustain animal populations for decades, if not centuries, to come. To quote Wild Tomorrow Fund’s Wendy Hapgood: ‘to save species, you have to save space for them.’