We always talk about there being ‘plenty more fish in the sea’ and our oceans are perceived as inexhaustible. An ecosystem covering almost three quarters of our planet, it appears too vast and too deep to possibly be in peril. Silently and steadfastly, oceans have absorbed more than 90 per cent of the global warming created by humans since the 1970s. And yet, less than three per cent of it is protected.

A Grave Prophecy

The controversial claim that ‘there will be no more fish in the ocean by 2048’ prompted a tsunami of debate when it was made in 2006. Backing the statement and delivering it to an even wider audience was Seaspiracy, the 2021 Netflix documentary that laid bare the fishing industry’s complicity in crippling our oceans.

So, 16 years on, does the claim hold any water, and are our oceans being destabilised by overfishing and a whole host of other environmental factors to a point where wild seafood does, in fact, cease to exist?

You only have to look to the tragic tale of Pacific bluefin tuna that’s been whittled down to a woeful 2.6 per cent of its historic population because of overfishing to realise that this critical ecosystem is dangerously out of whack

The man behind the grave prophecy is marine ecologist Boris Worm, Professor of Biology at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada. Together with 14 co-authors – including ecological economists and professors of marine conservation – he published the results of a four-year-long study in Science journal, which examined 7,800 ocean species from cyanobacteria to large fish.

Worm’s stark warning about catastrophic loss of fish species was the line the internet remembers even over a decade later. It wasn’t misinformation, but rather sobering stats, using global catch data sourced from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, and a time series of 12 different coastal regions around the world over the past millennia, that underscored the study.

The idea that we’re heading towards a complete collapse of marine life as we know it seems unfathomable. But you only have to look to the tragic tale of Pacific bluefin tuna, that’s been whittled down to a woeful 2.6 per cent of its historic population because of overfishing of it and its prey to realise that this critical ecosystem is dangerously out of whack. WWF has also sounded the alarm bells, stating that ‘more than 30 per cent of the world’s fish populations have been pushed beyond their biological limits and are in need of strict management plans to restore them.’

A Triple Threat

So why exactly is marine life so important to the health of our oceans, the planet and ultimately the human race?

First and foremost: food security. An estimated one billion people, largely from undeveloped countries, rely on seafood for protein. Fishing also accounts for the livelihoods of 11 per cent of the world’s population.

Our ocean’s health is also calibrated by marine life, which filters toxins from the water caused by pollution, reducing large-scale algae blooms. Feeding these uncontrollable blooms – sometimes called green or red tides – is chemical runoff from farms. The toxic tides slowly suffocate fish by depleting oxygen in the water, even going so far as mutilating their gills.

Meanwhile, the scourge of plastic – ranging from invisible microplastics to colossal floating trash –continues to wage war on our oceans. As recently as this February, the UN has been urged to curb the plastic trash epidemic with a historic treaty. Meanwhile, scientists at Tenerife’s University of La Laguna have identified a new type of emerging coastal pollution, they’re calling ‘plastitar’. Found on several of the Canary Islands, positioned on an oil shipping lane, it’s a toxic mix of hardened tar bonded with microplastics.

Pushing wild fish closer to the brink is climate change, threat number two. The world’s largest carbon sink, oceans are critical climate regulators. But our warming world is draining oxygen from them – the leading cause of destructive coral bleaching. This in turn impacts reef ecosystems that are responsible for maintaining marine biodiversity. Entire species are now under threat of being wiped out by oxygen-deficient ‘dead zones’ like the Gulf of Mexico’s, which measures 6,334 square miles. The damage doesn’t stop there. The ocean’s rising temperatures are even influencing the migratory patterns of species like the Black Sea Bass that’s moved some 200 nautical miles north since 1973.

The IUCN lists 77 per cent of oceanic shark and ray species threatened with extinction, in its red list assessment. Meanwhile, the Baltic Sea still has a massive dead zone the size of Ireland.

International Union for Conservation of Nature

Perhaps our ocean life’s biggest nemesis is overfishing, defined as when fish are caught faster than they can reproduce. Bottom trawlers are responsible for targeting multiple marine species. The process of dragging scars the seafloor, and many fish are discarded worldwide because they are the wrong species, too small or the fishing company is over quota.

A staggering 90 per cent of Britain’s offshore marine protected areas (MPAs) are still being fished with these ‘bulldozers of the seabed’, according to conservation NGO, Oceana. Worryingly, bottom trawling can still be categorised as ‘sustainable fishing’, which legally requires between 20-30 per cent of a fish stock to be intact.

Another commercial fishing practice resulting in huge fish yields but an indiscriminate loss of marine life is long-line fishing. Baited hooks are spaced out along lines that can extend up to 60-miles-long behind a boat, often resulting in incidental mortality of seabirds like the black-footed albatross.

Is a Sea Change on the Horizon?

Whether it was alarmist or not, Worm’s compelling statement still got people talking about the dire state of our oceans. ‘Biodiversity is a finite resource, and we are going to end up with nothing left … if nothing changes,’ Worm was quoted as saying. So, the question is, has much changed? As recently as this year, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists 77 per cent of oceanic shark and ray species threatened with extinction, in its red list assessment. Meanwhile, the Baltic Sea still has a massive dead zone the size of Ireland.

‘The challenges in the supply chains today are caused by businesses, and need to be solved by businesses. Technology has allowed us to begin raising the bar in terms of transparency in the supply chains’

Sheikh Fahim Al Qasimi

And yet, even Worm thinks all is not lost. ‘This can be done. It’s not beyond our reach at all,’ he’s quoted as saying. Also hopeful is Dubai-based entrepreneur Sheikh Fahim Al Qasimi, who’s on a mission to reform the seafood supply chain. ‘Our oceans are resilient and will bounce back if we continue to work towards our goals,’ he tells The Ethicalist when probed on the likelihood of fishless oceans because of overfishing.

Working out of a warehouse in Dubai’s Al-Quoz district, Sheikh Fahim’s startup, Seafood Souq, has developed a seafood traceability technology targeting fraud and wastage. ‘Fifty per cent of the seafood we eat is more like mining than farming. We extract it from the ocean, hoping that more will be there when we come back,’ he says.

‘The challenges in the supply chains today are caused by businesses, and need to be solved by businesses,’ he explains, continuing, ‘technology has allowed us to begin raising the bar in terms of transparency in the supply chains.’

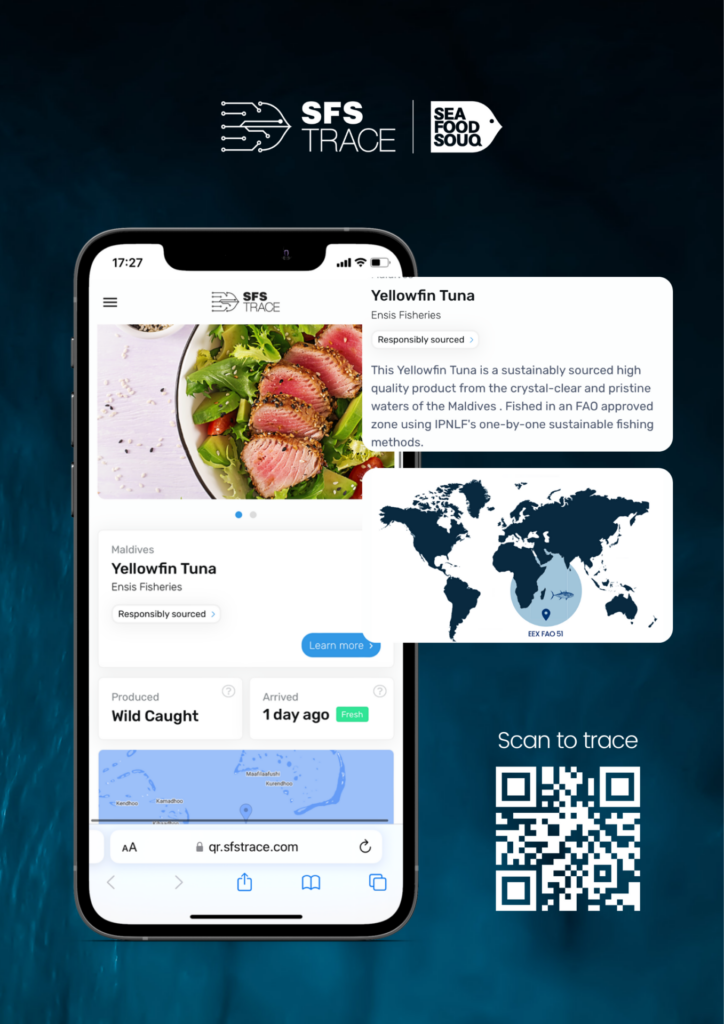

Seafood Souq’s tech SFS Trace (you can see a demo of how it works here) has already been deployed in four European countries and the company’s now collaborating with UAE’s largest supermarket retailer, as well a handful of the region’s leading hotels. According to the start-up, mislabelling of seafood in restaurants is rife. Seafood Souq’s game changing tech means ‘you can just scan a QR code [on the menu] to see exactly where your fish has come from,’ according to Qasimi.

Boasting some of the most sustainably managed fisheries on the planet, the United States has stamped out active overfishing in 90 per cent of stocks according to NOAA

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Worm’s grim prophecy assumes we do nothing to fix all the problems such as overfishing, but change is happening with the help of technology, activism and individuals like Qasimi. There’s no one clear-cut solution to restoring depleted or over-exploited fish stocks, rather it relies on a diversified approach.

Last year, Canada launched a $7 million programme that harnesses satellite technology to identify unregulated “dark fishing” vessels (defined as those which switch off location transmitters to avoid detection), targeting places like the Galapagos Islands.

But it’s the country’s southern neighbour that offers up one of the best lessons in how to win the war on overfishing. Boasting some of the most sustainably managed fisheries on the planet, the United States has stamped out active overfishing in 90 per cent of stocks according to NOAA (The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) data, with the help of catch shares: a form of property right to a fishery.

Meanwhile, Colombia has just become the Western Hemisphere’s first nation to protect 30 per cent of its oceans (well ahead of the 2030 deadline agreed on by 100 countries at last year’s 76th UN General Assembly), meaning oil exploration and fishing – not just overfishing –are effectively banned.

Perhaps most exciting of all is the prospect of a seafood dinner that circumvents oceans entirely. Despite being a few years off mass production, lab-grown sushi and crustaceans harvested from real fish cells is picking up pace on a global scale. Hope for marine life may be on the horizon after all…