Bowling along the dirt track, dust flying with every step, and under a sky so vast and low that I thought I could reach up and touch it, I couldn’t wait to see where I’d be living for the next six months.

I’d just arrived in Utende, on the island of Mafia, off the coast of Tanzania where I’d been working as a biology research volunteer for an NGO called Frontier.

Now I’d come to this fishing village to continue my research, studying fish population, and I looked around, taking in the wooden huts of the local fisherman and families, eager to know more. ‘It’s so quiet,’ I thought. I’d expected the stench of fish, the crash of waves and squawk of birds overhead as they circled, hoping to steal a morsel or two of the fishermen’s haul.

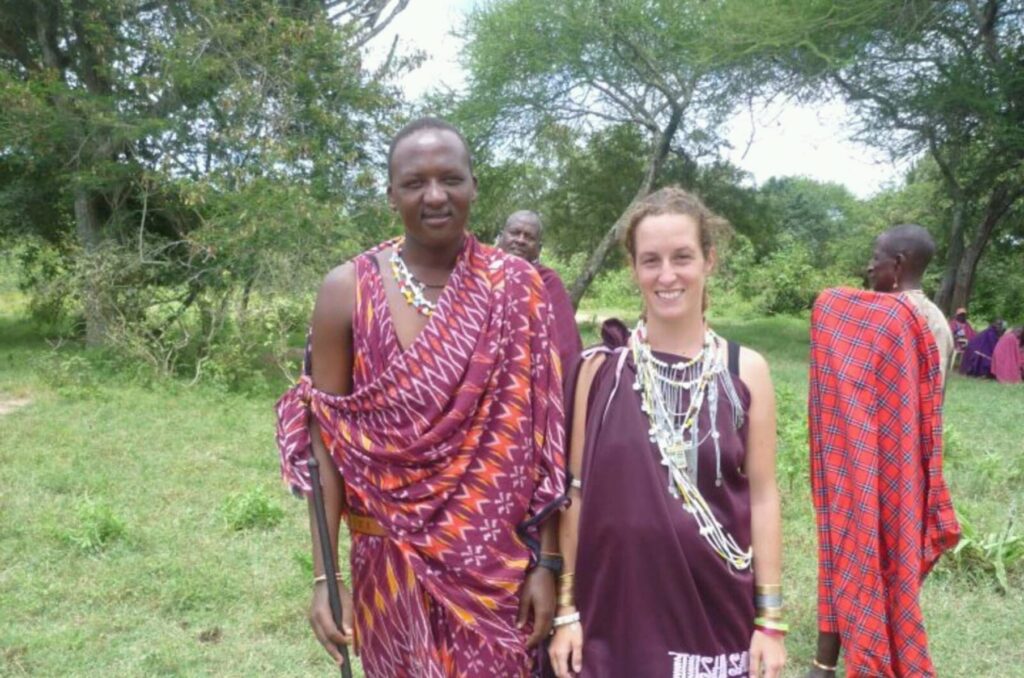

But we were actually slightly inland, where there was nothing but this sandy path, the traditional huts, and silence. The path took us up a hill, so carrying my bags, I began the ascent and then I looked up and suddenly there was only him. It was as if I had tunnel vision and couldn’t focus on anything but this one Maasai Warrior. He was walking towards us with two other Maasai, but I was fixated on him. He was breath-taking.

He was taller, and broader than the others, with a traditional red and purple cloth wrapped around his body. He was wearing anklets of white beads that glinted in the sun and reached up to his calves. In his ears dangled what looked like small white plates, blowing in the breeze.

‘Habari,’ I blurted out as he neared me, his eyes widening slightly at hearing this white woman saying hello in Swahili. ‘Habari,’ he smiled, getting ready to walk on.

We spoke in Swahili – he didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak his language, Maa – but what we didn’t know in words, we said in smiles and with our eyes. ‘So what are we going to do now?’ he finally said – and I didn’t know.

I stepped to the side, but I didn’t want him to go. I wanted to get to know him, find out his name. I wanted to stare into those cat-like eyes of burnished amber, but the trio seemed in a hurry. I watched him go, trying to shrug off the encounter, but inside I suddenly felt hollowed out, as if something was missing. Him.

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ I chided myself. ‘He didn’t even notice you. Forget about him.’ But he’d left a huge impression and I wanted to find out more about him and the Maasai. It didn’t take long. His name was Sokoine Papaa and he was a security guard at the local diving school.

Falling for a Maasai Warrior

Over the next six weeks, I’d go to a café near the dive school for a beer with friends I’d made on the island. As I walked along the beach, I’d yearn to catch a glimpse of him. When I did he’d smile, but that was all. ‘He’s not interested,’ I told myself, but still I’d go to the café, hoping to see Sokoine. He’d be in there with his friends sometimes, and I’d grin, trying to tempt him to sit with us, but the Maasai kept themselves to themselves and I realised it was utterly pointless.

But then one day as I tucked into a plate of chips, my friend Michael said: ‘Oh look, here comes your Maasai.’

I quickly turned my head to see Sokoine approaching. ‘Why do you say that?’ I said, confused. ‘Don’t you know?’ Michael said. ‘He likes you!’

Michael insisted that Sokoine had told people he liked me. It gave me the confidence to go over to him.

We spoke in Swahili – he didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak his language, Maa – but what we didn’t know in words, we said in smiles and with our eyes. ‘So what are we going to do now?’ he finally said – and I didn’t know.

The village was in the middle of the bush, where there were leopards, hyenas and, in the dry season, elephants. There was no running water, electricity, toilet or any of the things I’d been used to back in Germany, or even on the mainland of Tanzania, but I didn’t care.

I was out of my depth. I was 24 and from Frankfurt in Germany. I didn’t know anything but the basics about the Maasai culture. But I did know this wasn’t some holiday fling. We couldn’t toy with each other. We were in full-heartedly, or we had to walk away before it became complicated.

‘Give me a week,’ I told him. ‘I need to think.’ Being with Sokoine would mean immersing myself in the Maasai culture, one that’s a world away from the West. But I didn’t have to think for long. My heart told me my answer: yes, so I listened to it.

I went to find him. He led me to the beach. It was the first time we were together under the stars of the Tanzanian night sky. Holding his hand, I knew I was already in love with him.

It was March 2011 and I only had another three weeks on the island before I had to return to the mainland for a couple of months. ‘Come to my village when you come back,’ he said and I nodded.

Sokoine couldn’t read or write, but he asked his friend to send texts from his mobile phone. ‘I miss you,’ they’d say. ‘Me too,’ I replied.

Meeting the Family

Nerves and excitement swirled through me as we entered his village, Lesoit, on my return. I was going to meet his mum, dad, seven siblings and 14 half siblings. ‘My father has three wives,’ Sokoine explained. ‘I’m the eldest, the first born from his first wife.’ His family welcomed me with open arms. ‘You are our guest,’ his mother, Yayai, said.

We were allowed to sleep in the same hut, made of wood, sand and cow dung, as his family already saw me as his wife. The village was in the middle of the bush, where there were leopards, hyenas and, in the dry season, elephants. There was no running water, electricity, toilet or any of the things I’d been used to back in Germany, or even on the mainland of Tanzania, but I didn’t care.

Everyone spoke Maa, which I still didn’t understand and so we spoke Swahili. The Maasai were so different from anyone I’d ever known: gentle, noble and they treated me – the Western woman with no family as my single mother had died six months before I went to Tanzania – as one of their own.

That’s why after a few months of to-ing and fro-ing between Europe and the village, I decided in January 2012 to move there permanently. I knew it wouldn’t be easy to adapt to his culture but I needed to try because Sokoine didn’t want to live anywhere else, so this was the only way we could be together. And I couldn’t imagine life now without him.

So I went back, and we decided to get married. We didn’t need a piece of paper to prove how we felt about each other, but the truth was my visa was due to run out soon.

It didn’t sound very romantic saying ‘I do’ for a residence permit but I loved him and couldn’t have been happier. We had to go to a register office in Dar es Salaam on 8 February, 2012, so it was just the two of us with two witnesses. The night before we ate rice and I woke up in the early hours with food poisoning. I vomited all night, and wanted to crawl back to bed rather than get married, but Sokoine helped me there.

He wore his Maasai cloths while I was dressed in a green shirt, black skirt and flip flops. We didn’t have any rings or a bouquet of flowers. ‘I don’t care about any of that,’ I told Sokoine. ‘I just want you.’ He grinned. ‘You’re already my wife,’ he said. Afterwards I went straight back to bed as I felt so ill.

There weren’t any shops, TV or the internet, just my books to read. Instead there was so much beauty living in harmony with the wildlife and nature. A life where you walk 45 minutes to fetch water and cook over an open fire

Back with his family we had a huge Maasai ceremony in the April where a piece of bark from a tree was wound round my wrist and neck and an elder gave us a blessing. Everyone danced until dawn and we had beers and a lot of food. Sokoine gave me a cow as a wedding present along with my own goat. I called the cow Pesa which means money in Swahili.

Embracing Life Among the Maasai

I was now an official part of the family but it was hard adjusting. Even though I was surrounded by people, I was lonely and often felt out of place.

The Maasai way of life is slow, and resolves around their livestock so as soon as the animals are out grazing in the forest, there wasn’t much to do. There weren’t any shops, TV or the internet, just my books to read. But instead there was so much beauty living in harmony with the wildlife and nature. It’s a life where you had to walk 45 minutes every other day to fetch water for cooking and washing. A life where you cooked over an open fire and ate the same food – Ugali, a dish made with maize flour – every single day.

Yet, it was a life that was beautiful in its rawness. I watched animals give birth, first a sheep, then a cow and a dog, and then Sokoine’s cousin, Kaye, asked me to be with her when she had her first baby.

I was so honoured by this and in awe of how the women in the village supported and helped one another. It took me a few years but finally I was ready to be a mum, too. In May 2015, I became pregnant.

‘I’m going to be a father,’ Sokoine said, his voice tinged with pride. He loved seeing my bump grow, and later feeling the baby wriggling and kicking inside me. I bloomed out in nature, but I wasn’t prepared to give birth in the bush. I was scared something might go wrong.

So we went to the biggest hospital in Tanzania, where after 30 hours of labour, the doctor told me: ‘You need a Caesarean section.’ I was given a full anaesthetic as that is the norm there, and I woke up to find out I’d had a baby boy, Yannik.

We hardly saw him and there was no affection when I did. That was normal for the Maasai – PDAs are frowned upon – but I needed to feel loved by Sokoine. I did nothing, it seemed, except breast-feed.

‘He’s the most handsome baby in the nursery,’ Sokoine said, tears welling. I’d never seen him cry – in the Maasai that’s reserved for when people die. I couldn’t wait to hold our son, and when I did I looked into his face and thought ‘there you are.’ I loved him instantly, and stroked his handsome face and soft hair, drinking in his warm, milky scent.

Back in the village, my mother-in-law moved into our hut with me and the baby for three months while Sokoine went to stay with one of his brothers. ‘This is the custom,’ he explained when I looked upset.

I wasn’t expected to do anything except look after my son – Yayai and the other women did everything for us, but I missed my husband. We hardly saw him and there was no affection when I did. That was normal for the Maasai – PDAs are frowned upon – but I needed to feel loved by Sokoine. I did nothing, it seemed, except breast-feed.

‘It was why after we saw first-hand the effects of climate change in 2017 – when the rain didn’t come and our cattle got skinnier and skinnier in the drought and then starved to death – that I knew I had to fight for my family as well as the culture of the Maasai’

I didn’t even have any nappies to change – babies in the Maasai are simply allowed to go to the toilet freely and then are cleaned – but every day seemed to go on forever. I fell into a depression, a grim apathy that blanketed me. I wasn’t interested in anything. I was numb.

And then one day I thought: ‘You need to make a decision. Either waste your life away feeling like this, go home or surrender yourself to the Maasai culture.’ It was the only way to feel alive again.

For the first time I was torn between my European roots and my new life. But I loved Sokoine and our son. I couldn’t leave.

There was also something so special about the Maasai. Their culture was rich, and their roots deeply bound to the land they live on. It was why after we saw first-hand the effects of climate change in 2017 – when the rain didn’t come and our cattle got skinnier and skinnier in the drought and then starved to death – that I knew I had to fight for my family as well as the culture of the Maasai that I had come to love and respect so much.

I also started a sewing program with my sister-in-law Sendo, helping the women in our village make reusable sanitary pads, which we now distribute both locally and beyond.

They were the original guardians of this land and they needed to keep it fertile, and to save the environment from the devastating damage humans were making. I decided to create a crowdfunding campaign to raise money for our village leadership to attend a land management training course in Kenya that cost $5,000 (AED 18,350). That’s why I started my Instagram page @masai_story, which quickly amassed a following. People were fascinated with my life among the Maasai.

I also started a sewing program with my sister-in-law Sendo, helping the women in our village make reusable sanitary pads, which we now distribute both locally and beyond. I also started making YouTube videos about my new life, and I was asked to write a book, Maasai Story which was released on 21 May 2024.

Sokoine is proud of me. Our son is now eight, and is a Maasai boy, who speaks Maa, Swahili and English and can read and write.

I often get asked if I miss anything from my old life and I say: ‘What is there to miss?’ I might not have running water and walk around in dirty clothes most days of the week, but these things don’t matter. I’m with my family 24/7. I live with an incredible indigenous people who are resilient and care about the environment. I have more than most people ever get in a lifetime – I feel truly free. I am ha