The sight of a breaching whale launching itself into the air is one of the ocean’s great natural spectacles. But these critical ecosystem engineers don’t just rise to the water’s surface to breathe, they also come up here to poop – and rather than be disgusted, we should be grateful as that act underscores our planet’s very survival.

Known as the giant fertilisers of our world’s oceans, whale poop acts much like agricultural manure, feeding phytoplankton: a microscopic floating water plant that’s the base of all ocean food webs. These tiny drifting forests not only capture, process and store carbon, they also release oxygen back into the atmosphere and are responsible for most of the transfer of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to the ocean.

The scientific project has an ambitious goal: to help repopulate oceans and push their carbon capture to 50 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions by artificially encouraging the growth of phytoplankton with fake whale poop

But centuries of industrial whaling, combined with ongoing threats from ship strikes and entanglement in commercial fishing gear, has whittled down the world’s whale populations, leaving our oceans nutrient-deprived. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), six out of the 13 great whale species are still vulnerable or endangered. It can take decades for numbers of these slow-to-reproduce marine mammals to rebound. And time is something our oceans simply don’t have.

Cue synthetic whale faeces. Not some headline-grabbing gimmick, rather a very precise science designed to replicate as closely as possible the nutrient recycling service provided by whales.

Casting a Wide Net

Known as Marine Biomass Regeneration (MBR), the artificial whale poop project has been masterminded by Professor Sir David King: former Chief Scientific Adviser to the UK Government, and now founder of Britain’s Centre for Climate Repair at Cambridge University.

Six global universities and research centres, including the Institute of Maritime Research in Goa and the College of Cape City on the Southern Ocean, are also collaborating. Over the next three years, MBR plans to nourish areas of the world’s seas with a Pacific-bound vessel departing from Honolulu this September and the bi-ocean Western Cape earmarked for early 2023.

Their ambitious goal: to help repopulate oceans and push their carbon capture to 50 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, by artificially encouraging the growth of phytoplankton with fake whale poop.

To imitate whale faeces, the team will experiment with different compositions of materials that are naturally rich in nutrients like phosphorus and iron. Everything from agricultural waste to Saharan desert sand and volcanic dust from paradisiacal Tonga and Vanuatu islands in the South Pacific, are being considered.

April 2022 marked the team’s first mesocosm (an experiment designed to bridge the gap between a lab and the real world), which was undertaken 200 nautical miles off India’s southwestern coast in the Arabian Sea. ‘What we were doing in Goa was seeing if we could use rice husks as little rafts to float the artificial marine faeces,’ King explains to The Ethicalist.

‘The baked husks – a waste product sourced from a Goan factory – were filled with varying quantities of artificial whale poop made from iron ore and agricultural waste’, he says. ‘We’ve been doing a study of the deep oceans of all the world to see what nutrients are missing. In general, it is nitrates, phosphates, silicates and iron [which are all found naturally in whale poop]’.

The setup used a closed system of six bags filled with seawater on which the rice rafts floated. Over a period of three weeks, measurements were taken of the phytoplankton produced, which is responsible for roughly half of the photosynthesis on our planet.

Breaking down the Science of Whale Poop

King’s project focuses on Baleen whales, some of the largest animals on earth which include the humpback, blue and grey whales. They have ferocious appetites and what goes in must come out but the pressure at the bottom of the oceans prevents whales defecating down there so they have to rise to excrete near the surface.

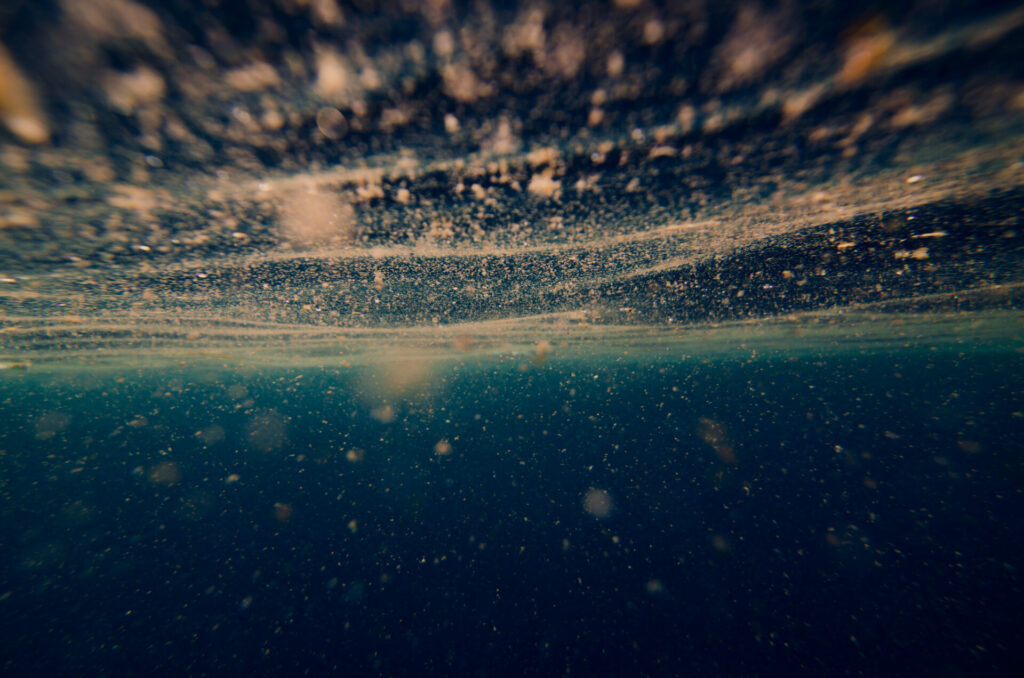

‘We always knew they come up to breathe, but what we hadn’t quite understood was the importance of their faeces being brought up to the surface of the ocean which is in sunlight,’ King explains. ‘If you get a pod of whales coming up, perhaps a 6,000 square mile area is covered with a thin layer of whale poop, and within three to four days that area will be covered in phytoplankton and zooplankton.

‘Fish larvae of all kinds of fish need phytoplankton [as their staple diet] so where there’s a phytoplankton layer, they all survive. So, you get this vast amount of fish – maybe up to half a billion fish – in that region. Within no time at all you have an ocean forest. That biosystem also produces krill for the whales. It’s a circular economy in the oceans.’

Put simply, without whale poop there is no phytoplankton, and without phytoplankton there is no krill: a tiny, shrimp-like crustacean found in all the world’s oceans, that almost every whale species depends on.

A Species on the Brink

Krill constitutes almost 100 per cent of the blue whale diet. As of last year, these graceful giants were classified endangered by The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Another beleaguered species seeing a startling decline is the North-Atlantic right whale, found predominantly off North America’s east coast. Named because they were considered the right whales to hunt because they floated when slaughtered, their population shrunk by eight per cent over the past year claims the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium, edging them ever closer to extinction.

Ship collisions, bycatch and other human activities account for an estimated 300,000 whale deaths every year. Gray whales and humpbacks are the most frequently reported species to be entangled, which slowly suffocates and starves them to death. Warming seas are also diverting whales from their familiar breeding grounds, with humpbacks predicted to shun Hawaii’s tropical waters because they are too warm, according to a new paper published by Frontiers in Marine Science.

The Carbon Connection

In the course of their long lives, whales accumulate carbon, which is safely sequestered on the seabed when their carcasses eventually sink to the depths of the ocean. One whale locks away a staggering 1,500 times the CO2 that a single tree absorbs in a year.

Also major mitigators of climate change, photosynthesising phytoplankton soaks up 40 per cent of atmospheric carbon dioxide.

But out-of-control algae blooms, caused by polluted waters, extreme weather conditions and when too many nutrients such as those found in the fake whale poop are available, can produce toxic compounds harmful to marine life and humans, while also blocking sunlight from reaching fish and plants – surely a red flag for King’s project? ‘Because [the experiments we’re conducting] are a natural process we’re confident there won’t be any significant damage at all, ’ King explains.

He’s a specialist in biomimicry, which means creating solutions by emulating nature’s best biological ideas. King also makes the point that his experiments will be conducted in the deep ocean, where any residual surface phytoplankton would sink to 800 metre depths. ‘Here the water is very cold and oxidation processes terminate, so the phytoplankton is sequestered [together with any carbon] forever,’ he explains.

The Sea’s the Limit

There’s a long road, or rather a vast ocean ahead for King and his team and their whale poop project. Crucially, they need permission from the London Protocol (one of two international ocean treaties created to control what waste is dumped in the sea) to progress the project at scale.

Although helpful, King explains that the data gleaned from their Arabian Sea pilot in Goa was impeded by a storm. ‘Ocean experiments depend critically on the weather,’ he says, adding, ‘the experiments are [being] staggered according to where the calm weather is.’

‘My ambition is to cover two-three per cent of the deep oceans surfaces every year [with a synthetic whale poop]’ King says, ‘we hope to return the global whale, fish and crustacean population to where it was.’

Which begs the question, could fake whale poop really buy our oceans some much-needed time, by allowing global whale numbers to rebound? King is hopeful, telling The Ethicalist, ‘Maybe in 30 years, we’ll have got to the point where whale populations have recovered to the point where we can leave the whales to act as the biological pump [the process by which the ocean uptakes excess atmospheric CO2 and sequesters it deep in the sea bed]. And they’ll get us back to pre-whaling conditions.’