Whales are some of the most important creatures on our planet, yet they are facing unprecedented threats. From habitat destruction and warming oceans to entanglement in fishing gear and noise pollution, these majestic giants are in danger of disappearing. Despite their struggles, whales play a crucial role in maintaining the health of our oceans. They capture carbon, stabilise marine food chains, and recycle nutrients, helping to regulate the planet’s ecosystems. Without them, the balance of our oceans, and our planet, would be at risk.

The tragic story of Tahlequah, a 27-year-old southern resident killer whale, highlights the urgency of the situation. In 2018, she made global headlines when she carried the lifeless body of her newborn calf for days after its death. With only 73 members remaining in her population, southern resident killer whales are critically endangered, and their survival is hanging by a thread.

Similarly, in February 2025, the mass stranding of 157 false killer whales on the remote beaches of Tasmania underscored the escalating threats to whale species across the globe. Despite extensive rescue efforts, many of the whales didn’t survive, and the tragedy calls attention to the broader environmental and human-induced pressures whales continue to face.

Despite their ominous name, killer whales, like all whale species, share many human-like qualities: they grieve, nurture their young, and live in complex social groups. However, threats like dwindling chinook salmon populations, noise pollution, ship strikes, and entanglement in fishing gear are pushing these creatures to the brink of extinction.

But efforts are being made to reverse this. From innovative fishing practices to international bans on whaling, there are increasing measures being taken to protect these ocean giants.

Whale Entanglement Solutions

Off Scotland’s west coast, one project – managed by the Scottish Entanglement Alliance (SEA) – is literally sinking ropes to slash the number of minke whales getting caught in fishing gear and creels – baited traps on the seabed used to catch shellfish like lobsters and crabs that often entangle marine animals, leading to injury or death.

‘Estimates indicate that in Scottish waters around six humpback whales, 30 minke whales and 29 basking sharks become entangled in creels each year,’ Bycatch Coordinator at Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC) Bianca Cisternino tells The Ethicalist. ‘Minke whales and basking sharks are generally not strong enough to escape from or swim off with [fishing] gear and instead die in situ.’

The project involved working with local fishermen to test sinking ropes that stay on the seabed, instead of floating ropes that can entangle whales. Over 1,500 trips were made using these modified ropes, and the results were encouraging. The fishermen reported few problems, and some even preferred the new gear.

Overall, the project has been hailed a resounding success, with ‘fewer tangles occurring, particularly during rough weather or strong tidal flows, potentially increasing catch rates and reducing habitat impact,’ Cisternino reveals. She adds ‘now that trials have been completed, work is underway to effect changes all around Scotland.’

Sinking ropes have been used in other parts of the world to help reduce whale entanglement in fishing gear. On the US east coast, sinking lines have been part of a broader effort to prevent entanglements with the endangered North Atlantic right whale. In South Africa, they’ve been used in the octopus fishery to protect Bryde’s whales, and so far, this approach has been successful, with no further entanglements reported.

10,000 miles away in the remote iceberg-strewn waters of Antarctica, the global appetite for krill is piling the pressure on whales. Every day an adult Antarctic blue whale needs to feed on 4.2 tonnes of nutrient-rich krill: a shrimp-like crustacean which is at the bottom of the marine food chain.

By no means an inexhaustible resource, krill populations have declined by 80 per cent since 1970 in Antarctica according to the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). A demand driven by aquaculture industries and nutritional supplements, everything from protein shakes to pet food contains these paper-clip-sized crustaceans.

In Antarctica, whales find themselves in direct competition with krill supertrawlers, that they also risk colliding with or getting entangled in the nets of. Last October, three humpbacks were caught in huge krill nets, leaving two dead and one seriously injured.

After filming krill fleets ploughing through megapods of feeding whales in 2023, International conservation organisation Sea Shepherd’s Allankay ship returned to ‘The White Continent’ at the beginning of this year to track more of these industrial krill-ing machines.

In January 2023, a paper published in Global Change Biology revealed a cold truth: that the culling of krill lowered humpback whale reproductive rates in the Western Antarctic Peninsula.

This is a saddening set-back for a species that is otherwise thriving. Humpback populations have made a remarkable global rebound – between seven and 12 per cent every year – with The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) downgrading them to ‘Least Concern’ in 2008. This is largely attributed to international protections and commercial whaling bans. But these majestic marine megafauna aren’t entirely in safe waters. Known for making some of the biggest migrations of any living mammal, their seasonal journeys are set to be made even longer by the cascading effects of climate change.

Saving Whales with Silence

Also undertaking marathon migrations between their feeding and breeding grounds are fin whales. On Spain’s Catalan coast, bioacoustics are helping safeguard the second-largest whale species on earth, who’ve been observed in a 12 by 15 miles stretch of coastal waters called Vilanova i la Geltrú, found 30-miles southwest of Barcelona. ‘This is the only area that we know of where fin whales feed in the Mediterranean Sea,’ Director of the Laboratory of Applied Bioacoustics at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia Michel André tells the Ethicalist.

André’s also the Founder and President of The Sense of Silence: a foundation that literally listens to nature with the help of passive acoustic sensors which monitor biodiversity from the Arctic to the Amazon.

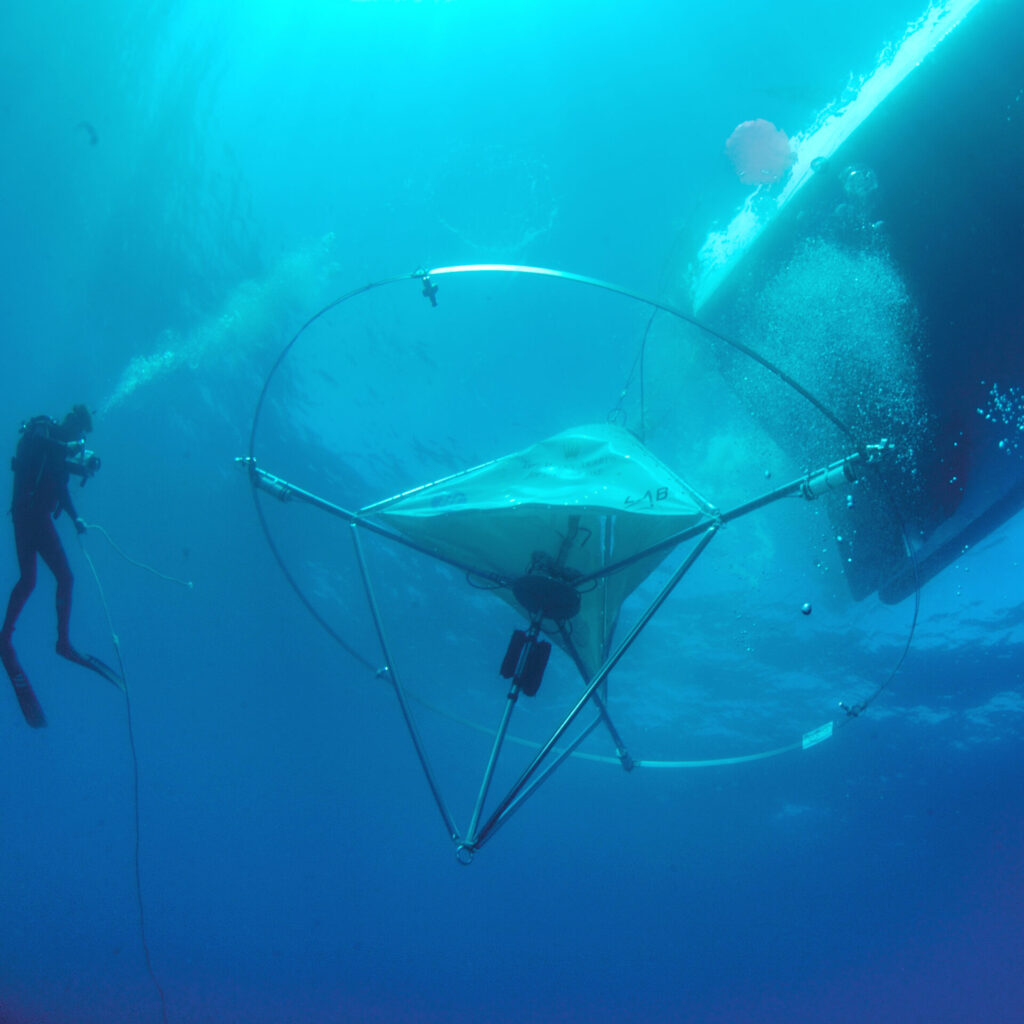

In Spain, André and his team’s non-invasive technology will help map marine biodiversity in the area by deploying underwater microphones – with robots and divers – to record the ocean’s acoustic environment.

‘We know that science goes faster than policies. We need more data to support the idea that this region specifically needs to be protected,”’ André says. Edging them one step closer is Vilanova i la Geltrú’s recent designation as a hope spot – a place identified as being critical to ocean health – by Mission Blue: the International marine conservation nonprofit established by legendary oceanographer Dr Sylvia Earle.

‘The hope is that eventually Vilanova i la Geltrú will become a MPA (Marine Protected Area),’ André says. In the meantime, the acoustic tech is going to be submerged in Vilanova i la Geltrú’s waters over the next few months, just in time for the migratory fin whales’ arrival in March.

Despite the challenges faced by these gentle giants, they continue to surprise conservationists with their resilience. Sei whales – one of the most poorly understood of all baleen whale species – are repopulating Argentina’s Patagonian coast a century after their near-extinction. Meanwhile, a spade-toothed whale found washed ashore in New Zealand last July marks only the eighth time in history that the planet’s rarest whale has been documented.

New legal protections are also painting a rosier future for these ocean guardians. Orcas, narwhals and sperm whales are now safeguarded under the UK’s Ivory Act, which previously only covered elephants. The expanded protection prohibits the the import and export as well as the trading of ivory (found in whales’ teeth and tusks) from all three species.

Here’s hoping that tougher legislations, more innovations and whale-safe fishing practices can help all species of these ocean guardians to follow in the flippers of their humpback cousins.