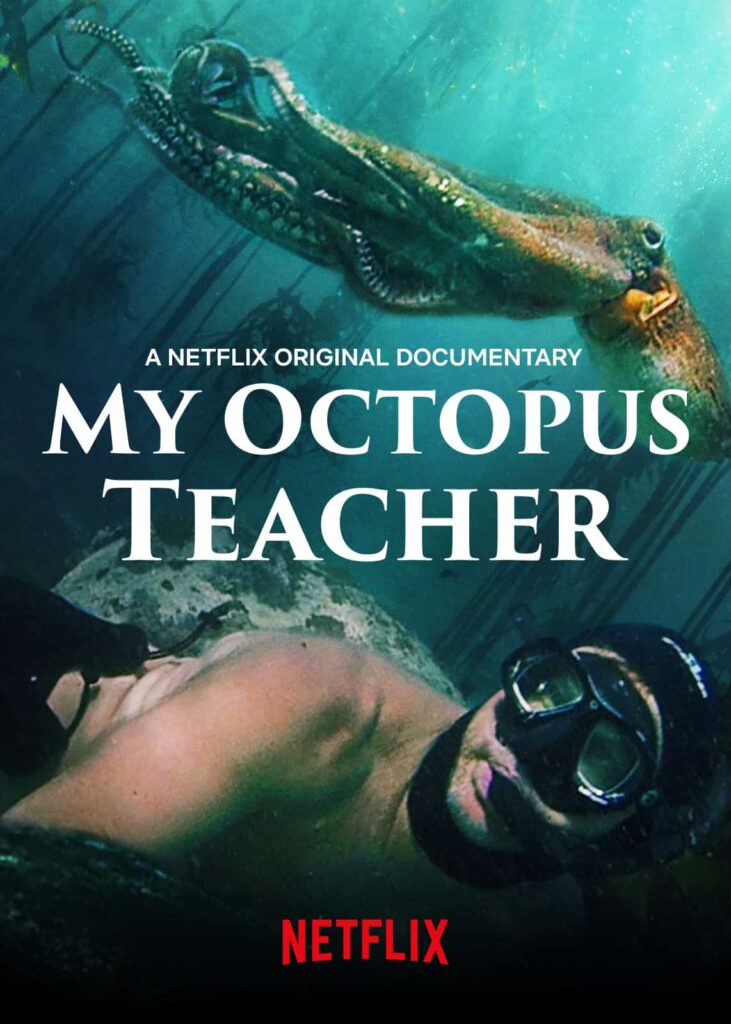

Anyone who has seen the Netflix documentary My Octopus Teacher will be in no doubt as to the intelligence and complexity of these remarkable creatures. The film, described as one of the most touching accounts of interspecies friendships ever to be recorded, tells the story of Craig Foster, who discovers a female octopus when he begins taking daily dips in the underwater kelp forests near his home in Cape Town, South Africa.

Over a year, the movie follows the deep bond that develops between the filmmaker and his subject. But the companionship between man and mollusc is only half the story. The documentary also reveals the incredible inner life of the octopus, intimately detailing the habits, personality, and ingenuity of the strange, shape-shifting sea creature.

For many who previously only knew octopus as an ingredient in Spanish tapas, the movie was a revelation, leading many viewers to vow never to eat pulpo again. One convert was billionaire Virgin businessman Richard Branson, who told Foster during a meeting that he hadn’t eaten octopus since watching the film and couldn’t see how anybody could after seeing it.

In 2021, octopuses were reclassified as sentient beings after a review of 300 studies found that they are intelligent and can experience feelings such as happiness or pain in a similar way to mammals.

Awareness of just how special these animals are has been growing, arguably since the publication in 2016 of the bestselling book, Other Minds in which author Peter Godfrey-Smith, a philosopher of science and experienced deep-sea diver, wrote about the incredible evolutionary biology of cephalopods. In 2021, octopuses were reclassified as sentient beings by the UK government after a review of 300 studies found that they are intelligent and can experience feelings such as happiness or pain in a similar way to mammals.

Biological Superpowers

So why is the octopus so special? They evolved down a unique evolutionary path that has given them a set of biological superpowers. They have light sensitive pigment in their skin which suggests they can ‘see’ with their tentacles. They can change colour, shape, and the texture of their skin to reflect their surroundings and mood. They are the most neurologically complex invertebrates, and two thirds of their brain cells are in their arms, which can think independently and problem-solve. They also have three hearts and can regrow severed limbs. Yet, for such unique creatures, they have a short lifespan of between one and two years and die after mating and laying eggs.

Octopuses do not cope well in captive environments. They become stressed, aggressive and cannibalistic, they don’t breed, are masters of escape and have been known to eat their own tentacles.

All this goes to explain why a plan to develop the world’s first commercial scale octopus farm has become so controversial, with animal rights organisations and scientists lining up to condemn it.

The plans have been lodged by Spanish fish company Nueva Pescanova who want to start production of factory farmed octopus in the Canary Islands. Earlier this year internal blueprints were leaked to the BBC that showed they plan to raise over a million of the intelligent creatures for food per year.

The farm in the Canary Islands intends to house the creatures in tanks of 1,000 in a two storey building, the documents show, leading to a mortality rate of around 10-15 per cent.

The animals would reportedly be fed with ‘fish discards and byproducts’ and would be killed by being placed in an ‘ice slurry.’

Octopuses do not cope well in captive environments. They become stressed, aggressive and cannibalistic, they don’t breed, are masters of escape and have been known to eat their own tentacles.

Spain, supported in part by the European Union, has led the way and experimental captive breeding programmes have been established in tanks on land, in open-ocean net pens, and on ‘ranches’ where wild-caught octopuses are raised in captivity. The Spanish Institute of Oceanography in Vigo has carried out most of the published research on octopus farming, but research is also occurring in Portugal and Greece, where the Mediterranean-based company Nireus Aquaculture has funded octopus-farming research.

Hunger for Octopus

The rewards will be substantial, as octopus meat commands a high price – wholesaling at around $7 a kilo – and octopuses reproduce and mature quickly, guaranteeing a rolling supply of stock. Despite the popularity of My Octopus Teacher, globally, the hunger for octopus meat continues to grow.

Octopus meat (pulpo in Spanish, tako in Japanese) has been buoyed by the popularity of sushi, tapas, ceviche, poke, and the desire for high protein, low fat food sources. According to data from the UN Food and Agricultural Organization, the global trade in octopus doubled from $1.3bn to $2.7bn between 2010 and 2019 with 420,000 tons of wild octopus landed globally in 2018.

‘Octopuses are recognised as the Einsteins of the sea and are capable of complex thought processes: they can navigate mazes, use tools, and learn how to do such things as unscrew lids simply by watching’

Peta spokesperson

That figure is expected to increase by 64 per cent by 2025 to 688,382 so Nueva Pescanova argues that its farm will not only fulfill demand for octopus meat but will also relieve pressure on wild populations and ‘protect a species of great environmental and human value’.

And while a director of Nueva Pescanova recently told Reuters that the animals would be constantly monitored and that stress on them has been ‘tremendously alleviated’, critics argue that octopuses kept in captive industrialised farms will live short, miserable lives.

Earlier this year animal welfare activists held a demonstration against the farm in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria and waved banners which read ‘Stop the Octopus Prison’ and chanted ‘they are not objects they are sentient creatures, their lives matter more than your money’. One of the groups involved was the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Peta), which has been lobbying the Government of Gran Canaria and Spanish ministers to ditch the farm plans.

‘These fascinating, highly intelligent animals should be respected and allowed to live their lives in their natural environments, not imprisoned and killed for tapas.’

A spokesperson told The Ethicalist: ‘Octopuses are recognised as the Einsteins of the sea and are capable of complex thought processes: they can navigate mazes, use tools, and learn how to do such things as unscrew lids simply by watching. They are masters of disguise, they decorate their homes as we do, and they have excellent memories.

‘They are also extremely sensitive to pain. Cramming these clever cephalopods into tanks or netted pools in which they would be denied everything that gives their life meaning would be unconscionable – which is why scientists, conservationists, and tens of thousands of PETA supporters are calling for plans for this octopus prison to be scrapped. These fascinating, highly intelligent animals should be respected and allowed to live their lives in their natural environments, not imprisoned and killed for tapas.”

Industrial Octopus Farm

Nevertheless, the drive to open the farm continues that Roberto Romero, Aquaculture Director says marks ‘a global milestone –It’s the first time that octopus will be raised at the industrial level.’

While the Spanish company may well become the world’s first large scale commercial octopus producer, a small octopus farm exists in Mexico where a biologist, Dr Carlos Rosas Vázquez, has been working with local fishing families for over 15 years to develop a captive programme in the coastal town of Sisal on the Yucatan peninsula. And while today his research project studies the effects of climate change on cephalopods, a spin-off initiative has developed a small-scale octopus breeding facility which the founders hope will eventually provide enough octopus to sell for food for the benefit of the local community.

The Mexico projects have been successful largely because the local species, the Maya, is particularly robust. Dr Rosas Vázquez told German public broadcast service DW: ‘The Maya is a very pleasant species. They have no problem being in the tanks together. They get along very well. They don’t emerge from the eggs as larvae but as fully developed tiny octopuses.’

This is significant because in previous attempts at captive breeding, massive numbers of octopuses died at the larval stage – even in the wild only one or two hatchlings out of 20,000 to 80,000 eggs survive until adulthood.

Despite these advances, many in the scientific community disagree with the fundamental argument that farming will work and will help conserve wild populations. A 2019 paper, The Case Against Octopus Farming, was published in the journal Issues in Science and Technology, by authors Jennifer Jacquet, associate professor of environmental studies at New York University, and associate authors, along with Walter Sánchez-Suárez, a PhD researcher at Mercy for Animals.

In it the authors argue that octopus farming has the same negative environmental consequences as other types of carnivorous aquaculture. Octopuses have a food conversion rate of at least 3:1, meaning that the weight of feed necessary to sustain them is about three times the weight of the animal.

The paper says: ‘Given the depleted state of global fisheries and the challenges of providing adequate nutrition to a growing human population, increased farming of carnivorous species such as octopus will act counter to the goal of improving global food security.’

The authors describe widespread observations of octopus as curious and exploratory creatures.

‘Once octopuses have solved a novel problem, they retain long-term memory of the solution. One study found that octopuses retained knowledge of how to open a screw-top jar for at least five months. They are also capable of mastering complex aquascapes, conducting extensive foraging trips, and using visual landmarks to navigate,’ the paper explains.

Cognitive Stimulation

‘Beyond their basic biological health and safety, octopuses are likely to want high levels of cognitive stimulation, as well as opportunities to explore, manipulate, and control their environment. Intensive farm systems are inevitably hostile to these attributes,’ it continues.

The authors argue that as consumers become increasingly concerned about animal welfare and sustainability, the case against octopus farming will become stronger.

‘If society decides we cannot farm octopus, it will mean relatively few people can continue to eat them. But it does not mean that food security will be undermined; it will mean only that affluent consumers will pay more for increasingly scarce, wild octopus,” they write.

In conclusion they call ‘for governments, private companies, and academic institutions to stop investing in octopus farming now and to instead focus their efforts on achieving a truly sustainable and compassionate future for food production’.

If octopuses can teach us anything, perhaps it is this, that the more time we take to understand and study creatures and their behaviour, the more we appreciate them and their right to a place in the world.