Bob Dylan’s reclusiveness may be legendary, but when, back in 2016, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, he stunned even his fans. How so? He said ‘no thanks’, to attending the prize-giving ceremony. For two weeks he hadn’t even responded to calls from the Nobel’s organisers, the Swedish Academy. Surely the message was clear.

Dylan’s eventual ‘no’ caused an international stir. For some Dylan deserved castigating for his adolescent rudeness, for his wild ingratitude. But for others – and precisely because most people like receiving accolades – it truly embodied some kind of rebel spirit, or what the French refer to as ‘je refuse’ – the right not to do something.

And yet, for humbler folk, it isn’t so easy, as four social scientists – including Amanda Cravens of the US Geological Survey Science Center, and Nicola Ulibarri, associate professor at the University of California Irvine – found out while conducting a simple experiment last year.

When, in 1967, the 25-year-old Muhammad Ali said he would not enter the US forces draft to serve in the Vietnam War, he was immediately stripped of his championship title and suspended by boxing authoritie

In a first of its kind study, they collectively denied 100 work-related requests and recorded their consequent emotions. Chief among these was what they call the ‘emotional labour’ involved in saying no – the associated guilt, the concern that one is letting others down, not doing one’s ‘fair share’ or failing to live up to one’s privilege, which seemed to be Dylan’s failing, as far as media coverage went.

Growing into No

Age and wisdom, naturally, may bring a greater willingness to say no without worrying about causing offence – as one saying has it, if at 20 you’re consumed by what other people think of you, at 40 you no longer care, and at 60 you realise nobody was thinking of you all along.

As the actress Sandra Bullock has said, her mid-life goal is ‘to remember every place I’ve been, only do things I love, and not to say ‘yes’ when I don’t mean it.’ But there is the sense that saying no is an option most readily available to the already powerful.

Indeed, saying no is an expression of that power – because to do so for those individuals invariably has no comeback. ‘The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say no to almost everything,’ as Warren Buffet has it. Well, easy for him to say.

But often saying no does come at a personal cost to even the powerful. When, in 1967, the 25-year-old Muhammad Ali said he would not enter the US forces draft to serve in the Vietnam War, he was immediately stripped of his championship title and suspended by boxing authorities, and effectively gave up his best fighting years. Again, saying no invoked outage.

‘We all know saying no is a hard thing to do, which brings with it some admiration for these people. But we like it because it also shows that there is always a choice, and that you don’t have to be defined by societal norms.’

Dr. Jessamy Hibberd, Author

‘The tragedy, to me, is [that Ali] has made millions of dollars off the American public, and now he’s not willing to show his appreciation,’ says the baseball legend Jackie Robinson. David Susskind, a TV personality of the time, called him ‘a disgrace to his country, his race and what he laughingly calls his profession. He is a simplistic fool.’

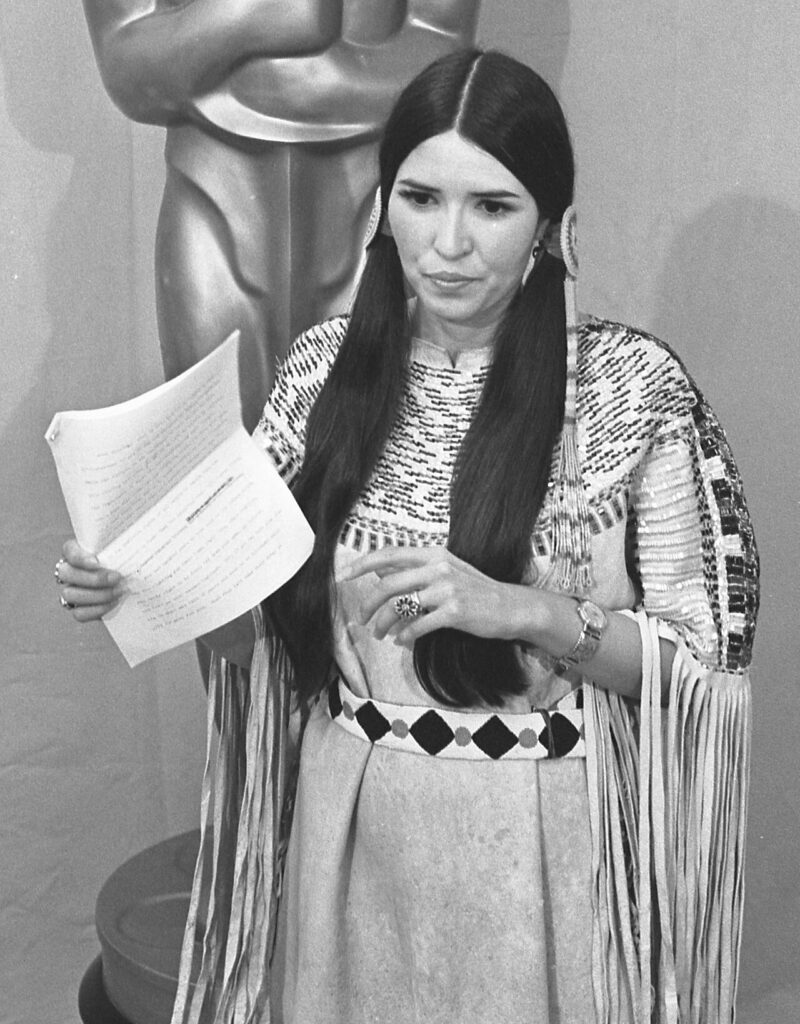

Others may not have risked jail, as did Ali. But certainly, they risked their careers. Fifty years ago this year, Marlon Brando may have become the best known of actors to have said no thanks to his Oscar win – in 1973 he sent a Native Indian representative in his stead and, to a chorus of boos from the audience, issued a statement about the misrepresentation of the United States’ indigenous peoples in the movies.

It’s such cases that are easiest to respect because, whether we agree with them or not, they’re an expression of a conviction in certain values, a conviction that carries some penalty. ‘We all know saying no is a hard thing to do, which perhaps brings with it some admiration for these people,’ suggests Dr. Jessamy Hibberd, a chartered clinical psychologist and co-author of the best-seller ‘This Book Will Make You Confident’ (Quercus) and of the forthcoming ‘How to Overcome Trauma and Find yourself Again’ (Aster). ‘But we like it because it also shows that there is always a choice, and that you don’t have to be defined by societal norms.’

Equally significant are the untold numbers of anonymous individuals who, over the years, have refused to recant their beliefs – be it in peace, science, or politics – and as a result suffered pariah status, if not imprisonment or death.

When we look back through history, we find figures like Galileo who stood firm against the authorities rather than deny the truth as they saw it. Equally significant are the untold numbers of ordinary people who, over the years, have refused to recant their beliefs – be it in peace, science, or politics—and as a result suffered pariah status, if not imprisonment or death. There can be seismic repercussions in even the humblest, yet often the bravest, of nos – as Rosa Parks and Claudette Colvin demonstrated.

Courage of Conviction

But why do most of us mere mortals have such a hard time saying no? Of course, arguably the gamble is greater when we most likely lack the advantages of position afforded the powerful. But the reasons run deep in our mental make-up as well. ‘We’ve evolved to be very social animals,’ explains Hibberd. ‘That was necessary for reproduction, for survival. Getting on with people – belonging – was essential. In that context, saying no can seem very risky. The assumption is that saying no leads to conflict. It’s why saying no as part of a group is that much easier – you’re not alone.’

Empathy means we feel the pain of anyone to whom no has been said as well – one more reason why we’re typically not so keen to say it ourselves, even to cold call salespeople. The latest medical thinking even suggests that social rejection can directly negatively influence our cognition and even physical health – rejection and physical pain activate many of the same parts of the brain – and in some instances can even prove a spur to violence.

After all, ‘unsociability’ is social media’s most heinous crime, its influence making it possible for someone speaking their mind – refusing to bow to received wisdom – to face ‘cancellation’ and career destruction.

One US study analysing school shooters found that, of 15, all bar two had suffered from social rejection; another study that the pain of rejection is no less intense even if that rejection comes from an individual or group we don’t even like.

If for most of human history we’ve lived in small, close-knit communities whose support may be vital to our well-being, no wonder that is a boat we don’t readily want to rock, or be rocked out of. This poses tantalising questions: whether increased urbanisation and with it, our letting go of a village mentality, will in time make us readier to say no.

Or whether, in a world in which social media has super-sized our village, making us more widely if superficially connected, we’ll grow ever more fearful of saying no. After all, ‘unsociability’ is social media’s most heinous crime, its influence making it possible for someone speaking their mind – refusing to bow to received wisdom – to face ‘cancellation’ and career destruction.

In the meantime, the scientists who conducted the 2022 study underscored that while there is plenty of logistical help available – time management tools, in effect – there is little emotional advice. So what could they offer?

They suggest that only a firm no works – a half-agreement to do something was a slippery slope; that providing a genuine and succinct explanation preserved relationships they might otherwise worry would be threatened; that relationships are improved with those who ‘respect our boundaries, personal lives and our sanity’; that having clear criteria as to the kind of invitation to accept and which to decline matter; and that practice in saying no makes it easier. Indeed, they noted that the more they said no, the more fully they were able to say commit to those opportunities they had said yes to.

‘People who can say no tend to use it, and so the ease with which it can be used becomes a virtuous circle,’ Hibberd agrees. ‘There are many reasons why someone may not feel comfortable saying no – a lack of confidence or self-esteem, because they don’t want to disappoint or have a need to be needed. But saying no is a skill you can teach yourself. You start with saying no to small things that don’t really matter, as a means of testing the water, and dissolving your fears of what might happen. And you build from there.’